The Monogamites vs. the Polygamites, Part 2

On the "Abraham Precedent"

This is the second of a two-parter. You can read Part 1 here. Some readers may need a primer to both essays. Here’s one I found to be helpful (in-depth and historical), and here’s another (short and to the point).

In Part 1, I argued that the debate over Joseph Smith’s polygamy is less about marriage customs and more about LDS prophetology. On one side, those who affirm Joseph’s polygamy acknowledge that he concealed his plural marriages from the public while he was alive. On the other side, those who deny Joseph’s polygamy argue that Brigham Young and the Twelve concealed its true origins by retroactively attributing D&C 132 to Joseph’s revelations after his death. Either way, the issue circles the same question: what does concealment (Joseph) or doctrinal retrofitting (Brigham) say about the trustworthiness of prophetic authority in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?

Some readers pushed back, suggesting that framing the question this way risks hardening it into a binary contest over which prophet lied. I get that, but it’s not the point I’m trying to make. What interests me here isn’t which side is correct—I don’t have a dog in the fight—but what prophetic concealment (Joseph) or misrepresentation (Brigham) reveals about how truth is conceived in Latter-day Saint prophetology.

So, to get there, in this second part, I turn to to what I call the “Abraham precedent”—the conviction that a prophet may conceal or misrepresent marital status as obedience rather than deceit, a protective duty justified by God. In this light, a prophet’s concealment of marriage—whether chosen or commanded—can be seen not as failure but as obedience, a safeguard until what he judges to be the appointed time for disclosure.

Admittedtly, I’m for sure not the first to notice this dynamic, but here I want to show how it speaks directly into present questions surrounding LDS prophetology. So, let’s begin with a question: What if, in the minds of Joseph and Brigham, the concealment itself of plural marriage could be understood as part of their prophetic role? What if they were sincere in their deception? And where would they get that idea?

(Personally, I don’t like that, but I’m not writing this essay to express what I think is right. I’m writing to express what I think Joseph and Brigham believed was right, and what such belief reveals about LDS prophetology.)

Ok, first up: the biblical stories about the prophet Abraham and his wife, Sarah (or, depending on how you read it, his sister.)

Abraham’s Half-Sister Wife

In Genesis 12, Abram (later Abraham) and his wife, Sarai (later Sarah), traveled to Egypt during a famine. Just before they entered, he expressed a concern:

“Look, I know what a beautiful woman you are. When the Egyptians see you, they will say, ‘This is his wife.’ They will kill me but let you live. Please say you’re my sister so it will go well for me because of you, and my life will be spared on your account” (Genesis 12:11a–13, CSB).

Basically, Abraham was afraid the Egyptians would kill him to ‘take’ her, so Abraham asked her to conceal their marital status by telling people she was his sister. Sarah agreed, and Pharaoh did, in fact, ‘take’ her into his house (you can read between the lines). But God intervened by cursing Pharaoh with some disease, so Pharaoh expelled Abraham and Sarah from Egypt, and actually enriched his wealth (12:16, 20).

I know… Über plot twist, right?

Notice how, in Genesis 12, deception is Abraham’s idea. It’s a calculated dodge to protect himself. The text frames the patriarch as fearful and self-serving, while God shields Sarah and intervenes for Abraham.

Now, you’d think this is the sort of thing a husband would do only once in his life. But apparently, if Abraham learned a lesson, it was the wrong one.

Genesis 20 finds Abraham repeating the maneuver, this time in Gerar. Again, he passed Sarah off as his sister, and again a king—Abimelek this time—‘took’ her. But before the ‘taking’ could be consummated, God appeared to Abimelek in a dream:

“You are about to die because of the woman you have taken, for she is a married woman” (20:3, CSB).

Abimelek immediately returns Sarah in the morning as Abraham’s ruse is exposed. Then, he gets even more stuff.

Notice how, in both episodes, God steps in to shield Sarah (12:17; 20:3–4). And just as striking, Abraham walks away not diminished but enriched. He actually gains wealth (12:16, 20; 20:14–16) and property (20:15). So, what looks to us like Abraham’s weakness turns out to be an opportunity for God’s protection and provision to Sarah and Abraham, respectively.

Unlike Genesis 12, however, chapter 20 clarifies the rational behind Abraham’s strategy. The prophet defends himself by a technicality. He tells the king:

“Besides, [Sarah] really is my sister, the daughter of my father though not of my mother; and she became my wife” (20:12).

So, he’s not outright lying. He’s just not telling the whole truth.

Moreover, Abraham framed this concealment as a good thing: a private, mutually agreed-upon act of “kindness” (20:13) between himself and his wife for his safety from outsiders. His fear, as he clarified, was twofold: first, that outsiders didn’t “fear God” (20:11), and second, that he was afraid for his life if his true marital status was known.

You might see where I’m going already: Abraham lied about his marital status because the truth could get him killed by outsiders. Joseph thought the same way.

Anyway, at this point, Genesis leaves us with a portrait of Abraham as a pragmatic prophet, i.e., a man willing to blur the truth of his marital status to preserve his life. The Hagar story (polygamy) complicates that legacy further, but we’ll return to it when Joseph himself does.

For now, concealment about marital status remains the central thread.

Abraham Did What Now?

Ok.

Admittedly, the Genesis 12 and 20 episodes are bizarre head scratchers. Naturally, they’ve left readers wrestling with Abraham’s integrity for generations.

Over the centuries, interpreters have tried to make sense of Abraham’s actions in different ways. Augustine argued that Abraham concealed rather than lied, preserving his honor by appeal to a technicality: Sarah was indeed his half-sister (20:12), a half-sister wife. (I checked—there’s no reality show called Half-Sister Wives, thankfully.)

Augustine put this interpretation forward as an apologetic against Manichean attacks on Hebrew scripture. They preferred their prophets neat and perfect, and instead of arguing for Abraham’s fallibility, Augustine argued for a technicality. His interpretation dominated for centuries, and it demonstrates an impulse in some biblical interpreters to clean up prophets.

By the medieval period, Thomas Aquinas advanced Augustine’s line by framing Abraham’s deception within moral theology. For Aquinas, Abraham “wished to hide the truth, not to tell a lie.”1 This distinction between hiding truth and formal lying was seen as a way for Abraham to maintain would become the ninth commandment while also safeguarding his moral integrity.

So, not only was it a technicality, but Abraham was actually pretty shrewd when you think about it.

The Reformers were less gracious. Martin Luther thought it obvious that Abraham was wrong for what he did. The prophet “willingly and knowingly exposes his wife to the danger of adultery,” in Luther’s eyes.2 John Calvin was equally appalled, opining how Abraham “although he did not lie in words, yet with respect to the matter of fact, his dissimulation was a lie, by implication.”3

It seems that most interpreters follow either the Augustianian-Thomist or Reformed interpretations. From my perspective, I think it’s a blend of both: Abraham may have played with technicalities, but if the point was to mislead, that’s de facto lying.

That’s where I land, anyway, but I also find myself drawn to a greater emphasis. When taken together, the Genesis 12 and 20 episodes highlight divine providence more than Abraham’s moral calculus. Abraham faltered, yes, but God protected and provided, rescuing Sarah and even enriching Abraham with livestock, servants, silver, and land (20:14–16). This reading shifts our eyes from Abraham’s concealment to God’s control.

In that sense, Abraham’s lack of forthrightness served the greater good of preserving his life, and God appears to have blessed the outcome. Still, the story remains odd—odd enough that later readers, Joseph Smith among them, would feel compelled to reframe it in their own way.

Joseph Smith and the “Abraham Precedent”

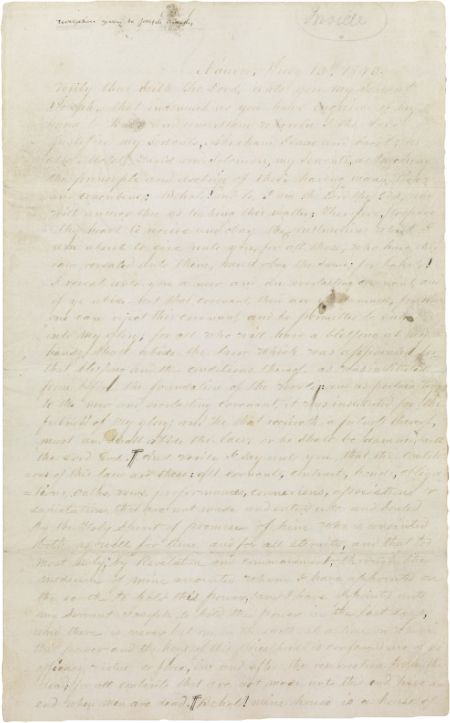

In the early 1830s, Joseph offered his own thoughts on the matter by revising the Bible in what became known as the Joseph Smith Translation (JST).4 In his rendering of the story, Abraham’s instructions to Sarah were ever-so-slightly reshaped. Where the King James Bible makes Abraham’s request sound like a calculated half-truth—“say, I pray thee, thou art my sister”—the JST instead has Abraham say:

“Say I pray thee unto them I am his sister that it may be well with me for thy sake and my soul shall live because of thee” (12:13, JST)

Notice how Joseph reframed that line, tweaking it from Abraham’s anxious request into Abraham’s script, i.e., he literally tells Sarah what to say. The difference is super subtle but very telling. KJV Abraham has Sarah claim a half-truth, but JST Abraham coaches her in the precise line she should deliver.

Why the change, and what’s the effect? Hard to say with any degree of certanty. But I do think it foreshadows Latter-day Saint men who would eventually coach their plural wives on what to say about their marital status. That works whether one believes Joseph himself rehearsed denials with his wives or, conversely, that Brigham pressured women after Joseph’s death into swearing affidavits under duress.

Anyway, Smith’s revision of Genesis shows him taking his first step in a centuries-long interpretive struggle: was Abraham lying (a la Luther and Calvin) or merely concealing (a la Augustine and Aquinas)? Joseph’s not ready to give an answer yet, but he’s certainly willing to maintain one fact about the story: Abraham chose to conceal his relationship with Sarah rather than risk his own life.

But, apparently, something about the story bothered Joseph. If, as God said to Abimelek, Abraham was “a prophet” (Gen. 20:7), then surely his actions had to be read through the lens of prophetic legitimacy, not moral lapse. A prophet might falter, but he couldn’t finally be framed as a deceiver (μὴ γένοιτο, apparently). So, why would the patriarch of God’s covenant people tell such a questionable half-truth?

The answer, for Joseph, came from the most unexpected place. In 1835, he purchased Egyptian mummies and papyri from an antiquities dealer, believing some of the fragments contained the writings of Abraham. He began translating portions with his scribes, publishing the results in 1842 as the book of Abraham in a church newspaper. The text was later included in the Pearl of Great Price and canonized by the LDS Church.

In the book of Abraham, the story is retold with a striking twist. No longer is concealment Abraham’s cowardly idea (Genesis 12) or even his “kindness” to Sarah (Genesis 20). Instead, God Himself commands it: “Let her say unto the Egyptians, she is thy sister, and thy soul shall live” (Abraham 2:24).

Here is Joseph’s answer to the interpretive question: was Abraham lying or merely concealing? Joseph says, “That question is relatively moot because God told Abraham what to say.” The coaching elevates from Abraham-to-Sarah to God-to-Abraham. So, what had been Abraham’s desperate ploy in Genesis is now recast as divine directive. The moral burden shifts entirely—Abraham is exonerated, but only by making God the author of the obfuscated technicality.

Obviously, this retelling presents a theological difficulty: it portrays God as directing an act of deception. Some Latter-day Saint interpreters have leaned on this to argue for exceptions to the general commandment against lying in moments of moral asymmetry, e.g., lying to the Nazis to spare the Jewish family hiding in your residence.5 I’m not entirely convinced—I think all lies still fall short of perfection and require forgiveness—but that’s beside the point of this essay. What matters here is the precedent the book of Abraham established for Joseph.

I think the most striking development in Joseph’s interpretation of Abraham came in 1843, when he received what became Doctrine & Covenants 132, i.e., the revelation on plural marriage that explicitly invokes Abraham as a divine precedent.

The revelation began with a question, with Joseph desiring “to know and understand” how or why God allowed the Old Testament patriarchs to take additional wives, e.g., Hagar.6 In D&C 132, Abraham’s plurality is explicitly justified. And if it was justified for the former-day patriarchs, then God could justify polygamy for the latter-day patriarchs.

The revelation doesn’t mention Abraham’s concealment, but given Joseph’s earlier interpretive work in the JST and book of Abraham, the precedent of concealment and the precedent of plurality now sit side by side. Together they form the theological scaffolding Joseph could lean on in Nauvoo: polygamy as righteousness, concealment as obedience.

Explained another way, imagine the former-day prophet, Abraham, in the mind of the latter-day prophet, Joseph Smith. What had been Abraham’s concealment in Genesis—recast as coaching in the JST and divinized in the book of Abraham—was, by D&C 132, expanded to embrace his polygamy as well. The Book of Mormon had condemned the practice, but also left a narrow exception (“to raise up seed”), and D&C 132 made that exception explicit: Abraham’s plurality was righteous. The revelation never mentions his half-truths about Sarah, but Joseph—having already reinterpreted those stories—could easily see concealment and plurality side by side, both framed as obedience to God’s purposes.

Taken together, these layers form the theological foundation for the Abraham precedent: the conviction that God may require a prophet to conceal or misstate his marital status to preserve life and mission.

Of course, one could just as easily argue that this sequence was less organic development than post-hoc rationalization, i.e., each step Joseph took conveniently prepared the ground for his later practice of plural marriage. But, proving Joseph’s intent with absolute certainty is nearly impossible.

Anyway, in this view, concealment isn’t an immoral lapse to be excused but a duty to be obeyed. It’s a sort of ‘noble lie’ for a greater good. Early Latter-day Saint obfuscation of plural marriage need not have registered to them as “lying” in the ordinary sense. Rather, they could’ve seen themselves as behaving consistent with a divinely sanctioned pattern, affirmed by their scriptures and reinforced by Joseph’s own translation work of a polygamous prophet as one.

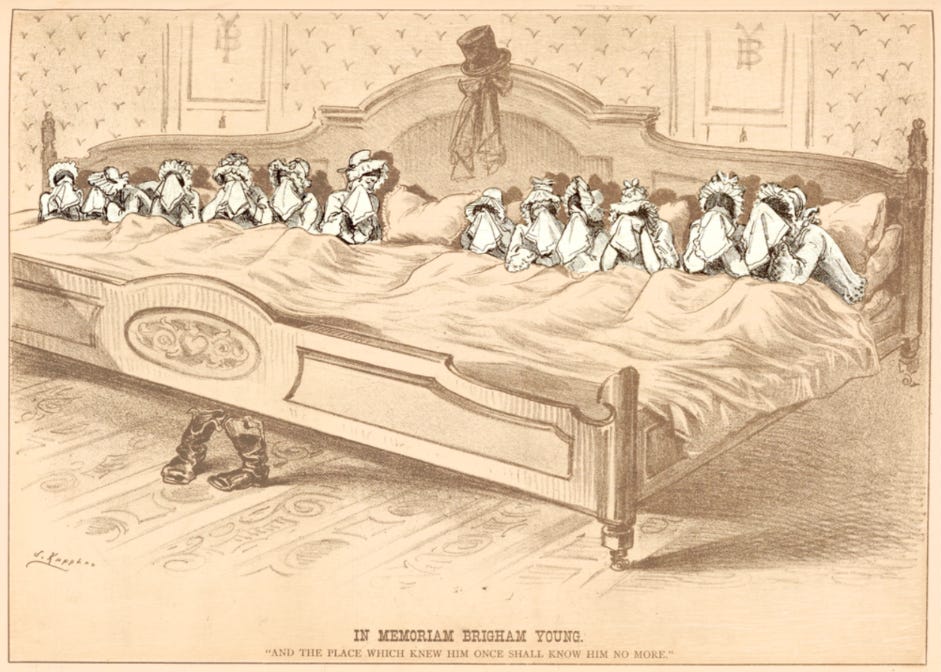

It’s no accident, then, that Nauvoo—where Joseph was privately practicing plural marriage while publicly denying it—became the proving ground for the Abraham precedent.

The Nauvoo Nightmare

By the early 1840s, Joseph Smith’s fears for his life and mission were hardly abstract. He’d already endured mob violence in Ohio, Missouri’s extermination order, and months in jail. In Nauvoo, rumors of his plural marriages spread like wildfire. Publicly he denied them, but privately he taught them as divine command to a select few. It was a dangerous balance legally, socially, and spiritually.

Naturally, he couldn’t prevent the tide of rumors.In fact, some of the fiercest opposition came from former allies—men like William Law, Joseph’s counselor in the First Presidency—who viewed the practice as corruption and proof that Joseph was a fallen prophet. So, when Law’s Nauvoo Expositor appeared in June 1844 with open accusations of adultery and deception, it struck at the core of Joseph’s fears. The exposé threatened his reputation, yes, but ultimately his safety.

“Surely the fear of God is not in this place,” Joseph must have thought.

This was exactly the kind of high-stakes environment where the precedent could take on immediate, personal relevance. If Joseph believed—based on his own revisions and the book of Abraham—that God had once commanded a prophet to obscure the truth about his marriage to preserve life and mission, then he may not have considered his public denials of plural marriage as immoral. They could have been framed as obedience, concealment as prophetic duty until what he saw as the “appointed time” for disclosure.

But, obviously, the precedent failed him. Abraham walked away from his obfuscations enriched. Joseph didn’t. The precedent couldn’t shield him from the fury of his critics, showing that what seemed theologically defensible in LDS scripture couldn’t bear the practical weight of Nauvoo’s dangers. Instead, accusations of polygamy became one of the central grievances that provoked the Expositor’s destruction and set in motion the chain of events that ended with Joseph’s death on June 27, 1844. The “appointed time” for Latter-day Saints to publicly reveal polygamy came only later, in 1852, when the Saints were secure in the Great Basin.

Even so, the Abraham precedent remains instructive. I don’t agree with the maneuver—nor do I particularly like it—but I could see how it could function to nuance the binary choice between “Joseph lied” or “Brigham lied.” On this reading, both men might have believed their concealment was not deception but obedience, i.e., an act of prophetic duty patterned on Abraham’s example (the JST-BofA-D&C Abraham, I mean).

And that’s the big point I wanted to make: their shared appeal to concealment reveals how truth itself could be conceived within Latter-day Saint prophetology.

Recall the scriptural pattern: Abraham could call Sarah his “sister” because they shared a father but not a mother (Gen. 20:12). It was a relationship real enough to claim, yet ambiguous enough to conceal. And in Joseph’s own retelling of the story, the book of Abraham went further still—God Himself commanded Abraham to misrepresent his marriage (Abraham 2:22–24).

That ambiguity offers a suggestive parallel to Joseph’s plural marriages. Under D&C 132, his sealings made the women his wives by revelation, but in civil law they remained unmarried. Like Sarah, their status could be told in two ways: wives in one sense, not-wives in another. In that sense, they were “half-wives,” a status that gave Joseph room to both affirm and deny the relationships, similar to how Abraham had done long ago.

So What?

The present polygamy–monogamy debate, then, isn’t ultimately about who was telling the truth. It’s about how truth itself is understood within a LDS prophetic framework. And that—not our historical verdict—is the far more interesting and important question that needs to be asked.

In traditional Christian theology, concealment about matters of divine command is usually treated as deception, and deception compromises the messenger. In the Latter-day Saint tradition, however, Joseph’s own scriptures establish that concealment, under certain conditions, can be commanded by God. That opens the door for a very different calculus, i.e., withholding certain truths could be seen as protecting God’s work rather than undermining it.

That brings us right back to prophetology. If concealment can be a prophetic duty, who decides when it’s permissible? How does the community discern between God-directed withholding and human self-preservation? And what happens to trust when members only learn the truth in retrospect?

The current debate may be framed around Joseph’s marital practices, but, in the end, it’s seriously probing the boundaries of prophetic authority itself, which, I think, is why things are so emotionally charged.

If the Abraham precedent helped Joseph reconcile secrecy with obedience, then Latter-day Saints today are left to decide whether that precedent still governs prophetic behavior today, and, if it does, what it means for their confidence in those who claim to speak for God. After all, Joseph’s scriptural productions built on one another in just this way—“precept upon precept, line upon line”—until both plurality and concealment could be counted as prophetic duty.

In the end, that’s the unresolved question: not simply “Was Joseph a polygamist?” or “Was Brigham lying about Joseph being a polygamist?” but “How far can a prophet go in concealing God’s commands before he ceases to be trusted as God’s prophet?” Until that question is faced head-on, the monogamy–polygamy debate will remain a proxy for a much larger conversation about the nature, scope, and limits of prophetic authority within Mormonism.

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk.

📘 Coming February 2026: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

Summa Theologica II-2 q. 110, a. 3.

LW 2:291

https://ccel.org/ccel/calvin/calcom01/calcom01.xxvi.i.html

Interestingly, Joseph left Genesis 20 relatively untouched. His revision only notes that Abraham “again” concealed his marriage and softened God’s tone in Abimelek’s dream by muting the severity of the warning.

For example, Duane Boyce argues that Abraham’s deception was morally justified because those who sought his life had forfeited their right to the truth, making such lies genuine exceptions to the commandment against lying (BYU Studies 61, no. 3 [2022]). In the end, Boyce says there is “no good reason to think that [Abraham] did wrong when he lied about Sarah.” Respectfully, I think this defense misses the forest for the tree: the narrative places Abraham in Egypt precisely because of his lack of trust in God, and his lie only compounds that distrust by seeking safety in deception rather than in God’s providence. To treat the episode as an authorized “exception” risks portraying the God of truth as inconsistent, commanding truthfulness in principle while sanctioning falsehood in practice. I remain unconvinced by Boyce’s interpretation, which seems compelled less by the biblical text than by the scriptural cards Joseph Smith dealt in the book of Abraham.

The revelation erroneously includes Isaac among a list of OT polygamists.

The concept of God commanding Joseph to lie to conceal a revelation is, perhaps, shocking at first glance.

But the very first couple of chapters of the Book of Mormon have Nephi committing a murder when he was commanded by God. (Of course, that entire story has been found to be perfectly biblically legal according to the laws of Moses. See Jack Welch). Certainly God has "excused" various sins to His prophets in the past; see Moses' killing of the Egyptian.

And is something a lie when it is both true and false? Consider the question: Was salvation available to people in 400 BC. The answer is yes and no. If you were a Jew, you could obtain salvation through the law of Moses. If you were a gentile... you were out of luck, aside from the very rare possibility of conversion to the Jewish faith, like Ruth did.

So if asked, Isaiah would say that Salvation is not available to the Babylonians. Is that a lie? Well... I don't know. It's both true and false, isn't it?

So when Joseph is asked about polygamy, it was certainly not a practice that anyone could do legally. Random church members were not permitted by God to enter into the practice, so it was not a recognized doctrine of the gospel. It was "by invitation only." Only in Brigham's time was it expanded to the Church.

I think we all have to remember that God, no doubt, has a different set of morals than what we have today. He, after all, is unchangeable and the same. He functioned perfectly well and declared His word to the ancients, in a time of blood sacrifice, polygamy, patriarchy, and widespread polytheism. He, apparently, was ok with Aaron offering sacrifices to the golden calf on behalf of the wicked Israelites... at least, Aaron wasn't killed for it. Such a thing is unimaginable for our conception of God today.

Joseph Smith once said, and I think this is something that no one could possibly disagree with, that "if you could gaze into heaven for 5 minutes you would learn more than has ever been written on the subject." Who could disagree? Whatever heaven is like, it will not be like America, circa 2025, with our twisted sense of morals.

God is the arbiter of what is right and what is wrong, and if He commands His prophet to conceal stuff, as he did to several Old Testament prophets, then that is the moral thing to do. He silenced Isaiah and Jeremiah, lest the people repent. That.... is not the common conception of God today, for sure.

I understand that you think Joseph's lying (or concealment) could have been commanded by God in an attempt to protect him or God's work. But what would Brigham's purpose for lying have been? And are you suggesting God could have commanded Brigham to lie about Joseph's polygamy?

I can understand the argument that God commanded Joseph to conceal his polygamy, though I don't agree with the idea that he practiced polygamy at all. I just don't see any other rationale for Brigham to have lied, except to legitimize and justify his own behavior.