The Monogamites vs. the Polygamites, Part 1

On Polygamy Skepticism and Prophetology in the LDS Church

This is Part 1 in a two-part essay. Some readers may need a primer for both parts. Here’s one I found to be helpful (in-depth and historical), and here’s another (shorter and to the point).

A debate is brewing within Mormonism that, at first glance, looks relatively benign. The question is simple enough, anyway:

Did Joseph Smith practice polygamy?

For most people, this question elicits a vague “Oh, yeah” recollection that Mormonism is somehow connected to polygamy, which then leads them to wonder whether Sister Wives is still running. (It is, for some reason.)

Within Mormonism though, it’s a different story.

A growing network of Latter-day Saints say he didn’t, and they’re challenging what many people (including myself) have long assumed to be settled history. The movement has gained enough steam that the LDS Church recently restated its stance: “Joseph Smith married multiple wives and introduced the practice to close associates.”1

Simple enough.

To lay out my cards early, in my reading of the historical sources, the evidence points to, “Yes,” Joseph did practice polygamy and introduced it to others. I’ve heard the arguments for a strictly monogamist Joseph, but have yet to be convinced. Admittedly, I’m far more familiar with polygamy in James Strang’s church than I am Joseph Smith’s, so I feel like I’m playing catch up. Still, I’m finding as time moves on, the more evidence is presented to argue Joseph was not a polygamist, the more convinced I am that he was.

But as I watch this debate unfold from my vantage point, I’ve come to the opinion that the core issue is less about 19th century Mormon marriage customs and more about prophetic authority. In other words, the debate is ultimately about what Joseph’s polygamy implies.

Someone isn’t telling the truth.

What’s At Stake

If Joseph was a polygamist, he was never forthright about it. In fact, on a number of occasions, he publicly denounced it. Perhaps the most famous moment was his tongue-in-cheek quip about being accused of adultery, of “having seven wives when I can only find one.”2 Joseph said this in May 1844, by which time, according to LDS and non-LDS historians alike, he’d already been sealed to more than two dozen women.3

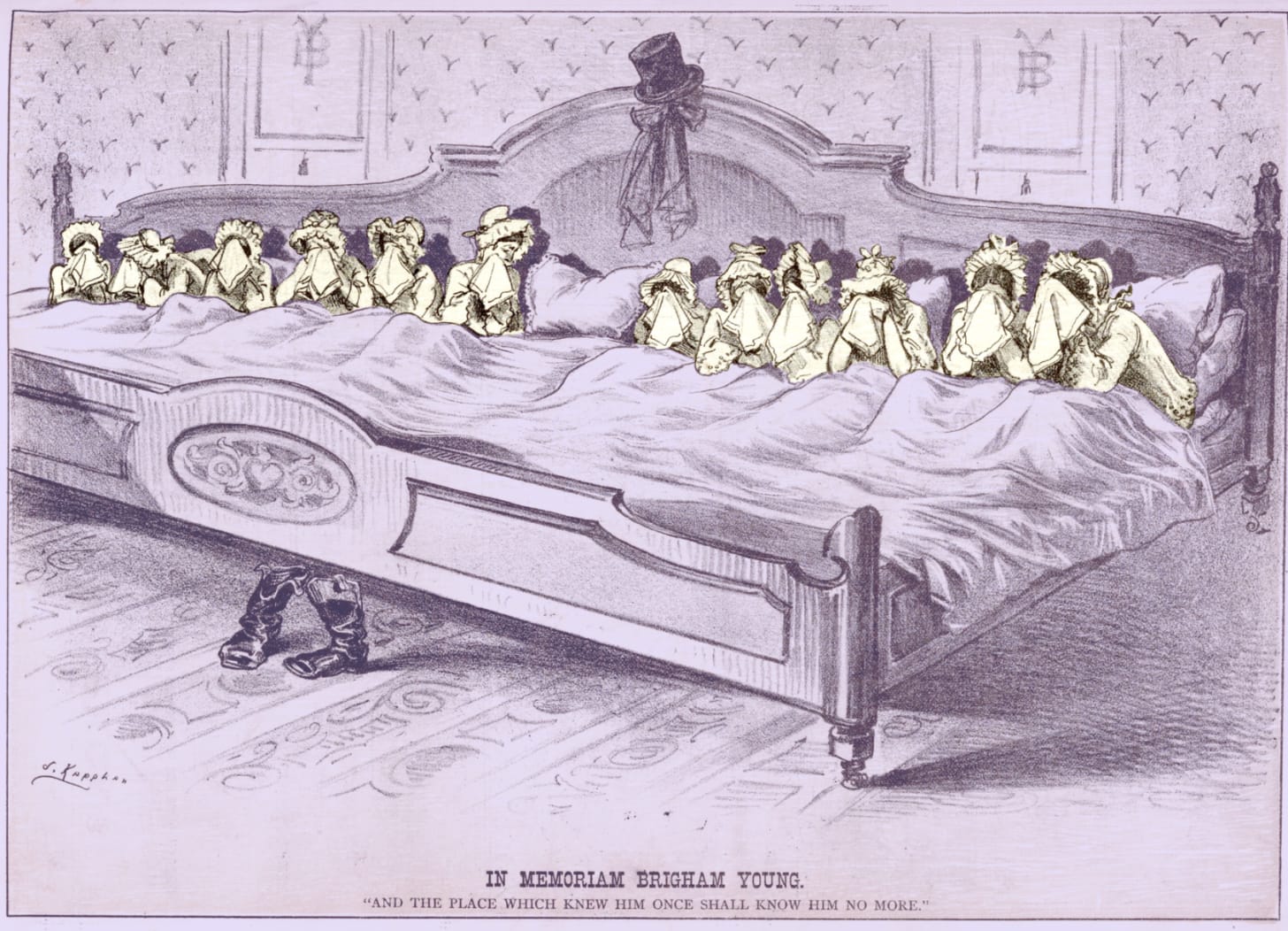

Brigham Young, by contrast, was far less guarded. After leading the Saints west, he openly defended plural marriage as a divine principle revealed through Joseph, and Brigham personally took more than fifty wives. He repeatedly insisted that Joseph had practiced the principle, even recounting conversations in which Joseph taught him its eternal necessity.

This creates an unavoidable dilemma. If Joseph practiced polygamy, then he deceived the public when he denied it. But if Joseph didn’t practice plural marriage, which was actually introduced later by Brigham Young (who retroactively retconned polygamy into Joseph’s revelations), then Brigham misled the Church.

So, it’s unsurprising to me that this dilemma is occasionally relegated to the broader principle that prophets aren’t perfect. Within LDS thought, prophetic leadership unfolds through continuing revelation given to imperfect people. Joseph himself once said “I never told you I was perfect,”4 and taught that a “Prophet is not always a Prophet” unless acting in that role.5 And modern LDS leaders have reminded members that not every statement by a Church leader constitutes doctrine. This framework helps members distinguish between prophetic opinion and prophetic revelation.

But while Joseph said he wasn’t perfect, in the same sentence, he also reassured his people “there is no error in the revelations which I have taught.”6 Prophets may not be perfect, but the revelations are. And that’s the problem: polygamy in LDS history isn’t a peripheral matter that can be safely filed under “prophetic opinion.” It’s bound up with eternal marriage, exaltation, and salvation, and it entered Mormonism as divine revelation, which eventually achieved canonical status (D&C 132). It touches on the very link between God and His people that the LDS Church teaches runs through priesthood authority and the living prophet.

This is why the issue cuts deeper than disagreements over Adam-God or the Canadian copyright. It goes to the heart of prophetic trustworthiness, and, therefore, to the heart of LDS prophetology itself.

Prophetic Authority as the Core Issue

In LDS thought, the priesthood is the plumb line between God and His people, and the living prophet is the principle earthly office in that authority. Continuing revelation through prophets is the hallmark of the faith. It shapes doctrine, directs practice, and sets the LDS Church apart from other Christian traditions. If any chain in that link of authority is weakened, people are less apt to trust it. But if the principle link is weak—if the prophet himself can’t be trusted—then to a faithful Latter-day Saint, the whole thing may feel like it’s snapping.

If Joseph was lying about polygamy, was he lying about the First Vision or Book of Mormon or eternal marriage? If Brigham was lying about Joseph, was he lying about everything else?

So, it’s better to think of the debate as a struggle over which prophetic legacy can be trusted. Should members stand with Joseph’s public denials of polygamy? Or with Brigham’s insistence that Joseph taught and practiced it?

Granted, I know that sounds overly binary, and I’ve noticed that people on both sides of this debate usually avoid stating their positions so bluntly. But when you follow their arguments to their logical conclusion, this is where they inevitably lead. And, to be very clear, I’m not suggesting that members are presently forced into this either/or choice. Rather, I’m observing that the logic of this particular debate seems to push toward such a choice, no matter how hard people push back, especially when it’s not even anyone’s intention to go there.

Frankly, I don’t envy faithful Latter-day Saints navigating this controversy. In a faith built on continuing revelation through prophets, questioning whether the founding prophets were truthful puts pressure on the core of everything the LDS restoration claims to be. It’s creating real division and straining relationships in real time. A historical question is becoming a test of faith, and members may soon find themselves forced to choose which prophet they believe.

And that’s an irony that I can’t shake.

The Monogamites vs. the Polygamites

Joseph Smith, as a young man, was unsettled by the divisions and bickering between Protestant denominations. In his 1832 history, he lamented that those of different sects “did not adorn their profession by a holy walk and Godly conversation” and his “mind [became] excedingly distressed” because he became convinced that humanity “had apostatised from the true and living faith.”7 To him, the divisions were obvious: “Priest contending against priest, and convert against convert,” each church “entirely lost in a strife of words and a contest about opinions.”8

That grief over division drove him to pray for clarity. The answer, he claimed, was the First Vision—Jesus Christ telling him that all existing churches were wrong and that none should be joined. Joseph’s later translation of the Book of Mormon echoed this theme, condemning the rise of “-ites” of every sort (see 4 Nephi 1:17)—i.e., sects and denominations—echoing the biblical urging for unity through “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (see Ephesians 4:5).

The persistence of denominations has ever since been a mainstay argument for the veracity of LDS prophetic authority.

Granted, I don’t like the divisions either. But traditional Christianity, for all its denominational differences, has historically rallied around a common authority: the gospel as preserved in the Bible and confessed in the ancient creeds. Latter-day Saints, however, look to living prophets as the touchstone unifier. When those prophets seem to contradict one another, that unity is tested. (Or, at least, I sense this is the direction the monogamy-polygamy debate is inevitably heading.)

And, so, a split emerges, creating two camps that, ironically, act as de facto denominations within Mormonism: the “Monogamites” and the “Polygamites.” Each insists it’s defending the true legacy of Joseph Smith.

Remember, too, that in LDS thought, denominationalism has long been taken as evidence that traditional Christianity forfeited divine authority. Yet, here the same dynamic appears inside Mormonism—a fracture over prophetic claims producing two de facto denominations. If division was once proof of lost authority in Christendom, what does division suggest about authority within the LDS Church today?

(LDS friends, please don’t read this as an apologetic jab. I’m pointing out an irony I think is worth self-reflection, returning a sincere courtesy for the many times I’ve been asked to account for the denominationalism of Protestantism.)

An Unresolved Prophetology

What we’re witnessing, I think, is an unresolved question at the heart of LDS prophetology, not just what a prophet is or does or can do, but what it means for a Christian church to be led by living prophets on earth. Can prophets err? If so, in what areas, how often, and in what ways? How do members discern between a prophet’s personal opinions and divine revelation? And when prophets seem to contradict each other, how should members respond?

To be fair, the LDS Church has tools for navigating prophetic fallibility, but I think they stop short of explaining what to do when a contradiction strikes at the very continuity of prophetic authority. Simply reaffirming the current position isn’t going settle the matter. In other words, it’s insufficient to summon a “Prophet is not always a Prophet” on this one.

So, given the current debate, what might an LDS approach to prophetology look like if it were developed enough to address such apparent contradictions head-on?

I’ll resist the urge to offer prescriptive solutions here, since it’s not my place as an outside observer. But I’ll note this: the structural differences between how traditional Christianity and Mormonism approach prophetic authority create different vulnerabilities.

Traditional Christians rarely think about past prophets—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Habakkuk, etc.—beyond what their revelations said about God, His people, and His messiah. We sing no hymns to prophets, our artwork rarely features them, and we seldom (if ever) measure our faithfulness by our spiritual alignment to them as individuals. Sure, we pour over their words in the Bible and commentaries, but not to hear from them but through them. After all, as John the Baptist said, “He [Christ] must increase, but I must decrease” (John 3:30). The prophetic role, for us, has always been to step aside so that the Lord Jesus stands foremost. We are led not by earthy living prophets, but by the gospel of the heavenly Prophet Jesus Christ (see Hebrews 1:1–3).

The LDS tradition, by contrast, regularly celebrates prophetic figures in song, imagery, curriculum, and conference addresses, which makes sense given the emphasis on continuing revelation through living prophets. They also view Christ as the Prophet, but see Him working in concert with—not in place of—those who hold the prophetic office today. That’s a completely foreign concept for traditional Christians, one that not even the Roman Catholic magisterium approaches in similitude.

This difference in prophetology shapes the way each community experiences questions of authority. When prophetic figures are so near to faith identity, as they are in Mormonism, contradictions between them become more destabilizing than they might be in traditions where prophets are viewed more as conduits.

This observation isn’t meant as cold critique but as analysis: different theological frameworks create different points of vulnerability. The current debate simply highlights one such vulnerability within LDS thought.

Anyway, and at any rate, I think this moment presents an opportunity for deeper reflection on the nature of divine authority itself. Rather than seeing this as a crisis requiring defensive positions, it might be viewed as an invitation to examine what provides ultimate spiritual certainty.

I’m not suggesting the debate end; rather, that it be couched as a subset of a more foundational issue—LDS prophetology.

Until Latter-day Saints can articulate a coherent framework for how prophetic authority works when prophets contradict one another—especially on matters claimed as divine command—the controversy over Joseph’s practices will remain a proxy battle.

Beyond the Binary (Looking Toward Part 2)

Until then, I’m sensing that the debate will eventually stalemate at a binary (no matter how hard researchers and historians will try to keep it from this): if Joseph was truthful, Brigham was not; if Brigham was truthful, Joseph was not.

But what if there’s another possibility, one that sidesteps the binary altogether (as a historical explanation)? What if both men believed they were acting under what they believed was a prophetic mandate to withhold or obfuscate certain truths for what they saw as a greater good?

In the biblical story, Abraham’s life is one of deep faith and glaring flaws. Twice, fearing for his life, he convinced his wife, Sarah, to conceal their marriage by emphasizing their blood relation. To later readers, the act was morally troubling, i.e., an apparent failure of faith that put Sarah in harm’s way.

In Joseph Smith’s revision of Genesis 12, however, the deception isn’t Abraham’s idea at all, but God’s command. For nineteenth-century Bible believers, this change resolved a moral dilemma but created a theological precedent: if God could direct a prophet to conceal the truth about marriage for the sake of life and mission, then divinely sanctioned obfuscation was possible.

That precedent applies uncomfortably well to the current debate. Could Joseph, or Brigham, have seen themselves acting in such a way, believing concealment was part of their prophetic duty? And if so, what would that mean for how we interpret their legacies?

In part two, I’ll explore this possibility and the canonical precedent that makes it plausible.

📘 Coming Soon: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic, this coming winter). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

“Joseph Smith and Plural Marriage,” https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/history/topics/joseph-smith-and-plural-marriage?lang=eng

Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, vol. F-1.

On generous research has shared a tone of resources gratis at https://mormonpolygamydocuments.org/.

Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, vol. F-1.

Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, 2:256.

Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, vol. F-1.

Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, 1:11.

Joseph Smith Papers, Histories, 1:208.