The 1824 Guide to Pronouncing Book of Mormon Names

Spoiler Alert: It Definitely Wasn't muh-ROW-nee

This essay is short and a bit quirky, but I’m in the home stretch of finalizing my presentation of the Gethsemane emphasis in LDS soteriology for my presentation at the upcoming Evangelical Theological Society meeting in Boston. I’ll post the Reader’s Digest version of that paper in the coming weeks. For now, enjoy one of the rabbit holes I went down when I should have been writing on other things…

Ok.

So, how do we actually know we’re pronouncing Book of Mormon names correctly? I mean, of course, besides consulting the LDS Church’s pronunciation guide or assuming ancient Semitic origins and working our way out from there.

I’m asking something more specific. If Joseph Smith or his earliest followers showed up at an LDS sacrament meeting today, would they recognize the way Latter-day Saints say Lehi or Nephi or Moroni?

The thought occurred to me recently while listening to a counter-cult “specialist” lecture on Mormonism.

It wasn’t… great.

The speaker postured himself as an expert, but clearly, he wasn’t. He claimed he was ex-Mo and close to “higher ups,” and maybe he was, but boy it just didn’t seem like it to me.

One of the giveaways was how he pronounced Moroni’s name. He didn’t say the standard muh-ROW-nai, but said it with an Italian flourish: muh-ROW-nee.

At first, I rolled my eyes and closed the tab. But then I started thinking. He was certainly wrong, but what if—by some broken-clock accident—he was wrongly right?

How did the original Latter-day Saint pronounce Book of Mormon names?

Let’s Ask John Walker

Fortunately, we have a resource from Joseph Smith’s own language world, a guide meant to standardize how English speakers pronounced words, including biblical names.

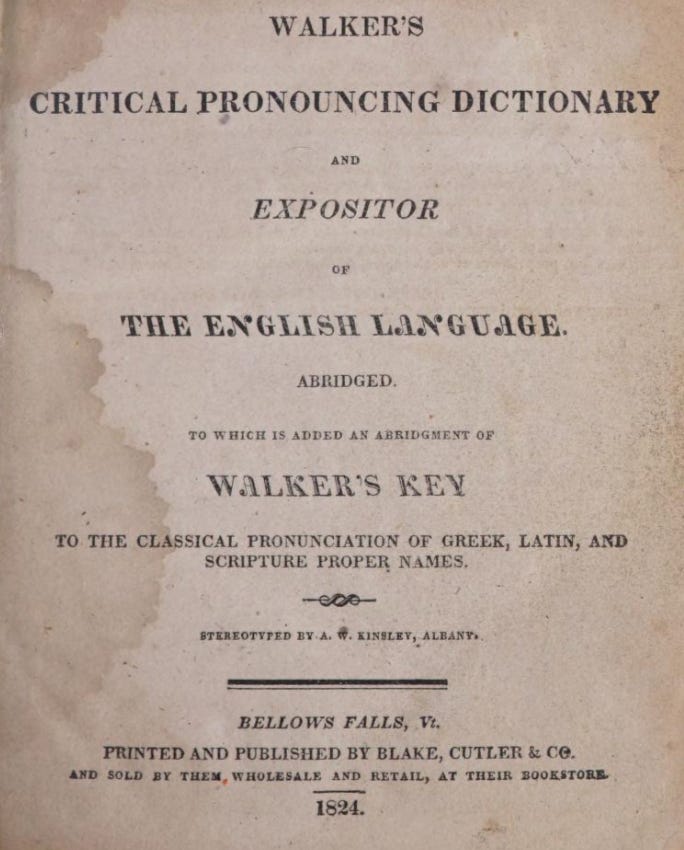

Years before the Book of Mormon appeared in print, John Walker’s Critical Pronouncing Dictionary was circulating in America. It was originally published in 1791 (I think) in London, but an American edition (Vermont) was printed in 1824, and another in 1830 (New York).

It’s a fascinating read because Walker’s work belonged to an era before British speech “classed up” with its later Francophilic refinements. In both Britain and America, pronunciation still carried the crisp consonants of pre-Victorian English, not the softened forms that would later make “British” sound like Bri’ish and “little” like li’ul. (For a people who like tea so much, it’s strange to me that they don’t pronounce the t.)

Walker’s goal was to provide a reliable, standardized guide for pronouncing English words. Conveniently, the dictionary ends with a section devoted to the proper names of the Bible.

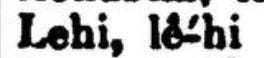

Now, whether or not people strictly followed Walker’s prescriptions is less important than what his guide reveals. His book shows how educated English speakers of Joseph Smith’s generation were expected to pronounce biblical names, giving us a basic linguistic baseline for how Joseph and his contemporaries likely said names such as Lehi, Nephi, and Moroni.

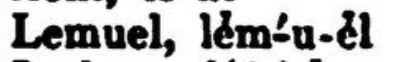

Walker provides the phonetic framework of what “sounded right” to an early-nineteenth-century ear. Names ending in -i, -iah, or -el would have followed an established convention. When compared side-by-side with modern usage (e.g., Adonai, Jeremiah, Daniel), those conventions remain remarkably consistent.

This matters because some Book of Mormon names match biblical names directly or contain recognizable biblical components. And when Walker’s biblical pronunciations are compared with those in the modern LDS pronunciation guide, the alignment is striking, especially when the Bible and the Book of Mormon share names.

This suggests early Latter-day Saints inherited, rather than invented, their pronunciation system for the Book of Mormon. They read scripture aloud in the cadence of King James English, absorbing pronunciation through sermons and public reading. So, when new names appeared, especially those shaped with familiar biblical endings, they naturally mapped them onto the sound system they already knew.

What About Moroni?

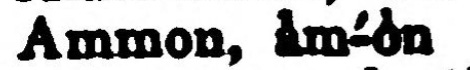

Here’s the rub, though: Moroni doesn’t appear in the Bible, which means there isn’t a direct biblical equivalent to cross-reference. But its form isn’t unusual if you’re familiar with Walker’s guide. Names ending in -i are consistently treated with the long ī sound.

Lehi? Long ī.

Nephi? Yes, again, long ī.

Amaleki? Long ī, once again.

See the pattern? Biblical names like Levi, Eli, and even “Ai” receive the same treatment.

Within that world, a final -nee sound simply doesn’t fit the established pattern.

So, when the earliest Latter-day Saints encountered “Moroni,” the most natural, instinctive choice would have been to apply the familiar rule: long ī at the end.

And since modern LDS pronunciation preserves that long ī sound—muh-ROW-nai—it is, I believe, closer to how the first readers and hearers would have pronounced it.

In other words, the contemporary pronunciation follows that old pattern, i.e., we’re saying it right. Moroni would have been pronounced the same way we say it today, with with the long ī sound, not -nee.

So, no, the earliest Latter-day Saints were almost certainly not saying muh-ROW-nee. (Sorry, counter-cult guy.)

Alright, what began as an eye-roll at a YouTube lecture turned into a small linguistic archaeology dig, but, hey, I think it was worth the spade and dirt.

Hope you enjoyed it.

📘 Coming February 2026: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

You found two of my biggest pet peeves in one person: 1. Claiming to be an expert when you're clearly not. 2. Claiming to be "ex-Mormon" when you're DEFINITELY not. They're two variants of the same problem, really; lies to present a false sense of trust and reliability.

The only thing missing (and maybe he said this, too, but you didn't write about it), is to say that "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints" is our recent rebranding to seem more Christian. Nevermind that it's been THE name for nearly 200 years.

It's as though the guy has a speech full of confirmation bias offered to those who already agree with him. For as much as it bothers me that his seemingly only familiarity with the "oni" combination in written form is via "macaroni", lying about past membership is worse. I see it too often. Some people genuinely left the church and are all about new beliefs now. Others just make blanket claims about past membership that we're supposed to accept on face value but as soon as you scratch beyond the surface it's apparent that it's just a role they're playing. If you need to lie about who you are in order to feign credibility, you're just admitting we shouldn't listen to you. It's why I'd MUCH rather than people spend time on "Here's what I believe and why. Let's discuss." instead of "Here's why you're wrong and going to Hell and stuff, but I say it out of love".

I'm reminded of a video I saw not long ago. Rather, it was a video wherein these guys critiqued someone else's video and that someone else was VERY guilty of saying "muh-ROW-nee" whilst claiming past church affiliation (or at least proximity). It may well be the same guy you wrote about.

https://youtu.be/CpkOdydqDV4

Note: growing up, PLENTY of people misread MANY words in both the Bible and the Book of Mormon. I can't tell you how many times I've heard Nephi as "Neffy". So they didn't reference the pronunciation guide, maybe never read it aloud before, I don't know. But those people don't prop themselves up as experts. Meanwhile, the names and words in the Bible I can't pronounce correctly would fill their own book. Doesn't mean I never read it. Just means I'm guilty of not learning good pronunciation.

Didn't expect this take. You totally nailed that 'fellow Mormans' observasion. So good!