More Than the King James

Pastoral Reflections on the LDS Church’s Updated Translation Guidance

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has clarified its position on the personal use of English Bible translations other than its preferred version, the King James Bible.

The updated General Handbook reiterates that members should “generally” use Church-published editions of the Bible in classes and meetings. For English speakers, that still means the KJV. That preference remains in place for practical and doctrinal reasons, e.g., there’s something instinctively familiar to a Latter-day Saint about the “Holy Ghost” that the “Holy Spirit” doesn’t quite carry in the same way.

But here’s what’s new, and why the change is noteworthy. The handbook now states:

“Other Bible translations may also be used. Some individuals may benefit from translations that are doctrinally clear and also easier to understand.”

That clarification matters because it explicitly applies to Church classes and meetings, not just private study. In other words, consulting other English translations is now publicly acknowledged as legitimate and sometimes even beneficial within official LDS Church settings.

The KJV remains the common baseline for the LDS Church, but it’s no longer the only permissible voice in the room.

And that’s what caught my attention.

Why?

Because as beautiful and historically formative as King James English is, language doesn’t stand still—it grows, changes, evolves. For modern readers, the King James Bible often introduces a secondary layer of interpretation: the biblical text moves from Hebrew and Greek into seventeenth-century English, and only then into modern understanding. That additional step can obscure meaning rather than clarify it.

Contemporary English translations attempt to remove that soft interpretive filter by translating directly into living English. They don’t eliminate interpretation, no translation can—but they do reduce the distance between the ancient text and the modern reader.

Here are my thoughts.

#1 A Pastoral Response

First, and most importantly, this lands on me pastorally.

I’m genuinely glad for Latter-day Saints. I love the Bible. As a teaching pastor, I spend most of my waking hours reading it, studying it, teaching it, and trying to help others hear it clearly. Not because it always says what I want it to say, but because it does its work on me whether I welcome it or not.

Sometimes the Bible confronts me, breaking through stubborn pride and self-deception (see Jeremiah 23:29). Sometimes it exposes what I’d rather keep hidden, judging motives and intentions I’ve learned to excuse (see Hebrews 4:12). Sometimes it simply gives light enough for the next step when the way forward feels dark and confusing (see Psalm 119:105). And when I’m worn thin, my prayer often reduces to simply asking God to comfort me by his word (see Psalm 119:28).

Why does the Bible do that?

Not because it’s magical—it’s not some codex of enchanted spells—but because the Bible is breathed out by God and bears the mark of his Holy Spirit who inspired it (see 2 Timothy 3:16). Even in its hardest passages, I find correction, instruction, and again and again the contours of the Lord Jesus himself, e.g., his is the ark to hide in, the lamb slain, the rock struck, the better king, the suffering servant. The Bible is ordered around him. He is the Word of God, the one through whom God speaks and acts, the one who makes God known to us (see John 1:1–3).

Clarity matters because knowing Christ clearly draws us nearer to him. Obscurity rarely deepens devotion; it usually just exhausts it. For that reason alone, I’m glad when unnecessary barriers to understanding are removed, even when those barriers are beautiful and long-cherished as the KJV language is for many.

#2 More Permission Than Prescription

This change is less direction than it is permission, perhaps even reassurance.

Many Latter-day Saints have long consulted other English translations in private study, especially younger members and teachers who find the KJV’s English more an obstacle to overcome than simply illumination to behold.

So, what’s really changed is the removal of a quiet ambiguity: the LDS Church has said plainly that clarity in reading the Bible is a legitimate goal.

The update went further still by listing specific recommended English translations. Without formally endorsing them, the handbook names several as helpful options:

English Standard Version (ESV)

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

New International Version (NIV)

New Living Translation (NLT)

New King James Version (NKJV)

And for children, the New International Reader’s Version (NIrV)

So, that feels less like bare permission and more like invitation.

#3 The Eighth Article of Faith Remains

Some reactions to this change have quickly pulled up the LDS Church’s 8th Article of Faith: “We believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly.”

If multiple English translations are now allowed, does that amount to an admission that they are “translated correctly” to the LDS Church’s standard?

No, and obviously not.

The handbook’s recommendations come with a clear qualifier: only “editions of the Bible that align well with the Lord’s doctrine in the Book of Mormon and modern revelation (see Articles of Faith 1:8)” should be used. They literally point members to the 8th.

So, nothing’s been abandoned. The 8th Article remains operative.

What has changed is how it functions. Rather than serving as a blanket suspicion of modern translations, it now operates as a criterion for Latter-day Saints. Some translations serve clarity and understanding better than others, and comparison can help readers see that.

#4 Addressing Other Reactions

Some evangelicals worry that accessible English Bibles blur the line between Mormonism and traditional Christianity, but I’m wary of that concern. Its practical implication is that Latter-day Saints should not read the Bible clearly lest they sound “too Christian.”

Interestingly, that instinct isn’t new. Just recently, I stumbled across an example. In 1884, an evangelical missionary in Calcutta complained that LDS missionaries confused locals because they “use the current language of evangelical Christians very glibly” (Christian Cynosure, December 18, 1884). The problem then, as now, wasn’t the Bible itself. It was shared vocabulary resting on very different assumptions about canon, authority, and how the Bible functions in the life of the LDS Church. If the solution is to prevent Mormons from reading “our” translations rather than clarifying the differences with them and others, then that response misses the point.

On the LDS side, I’ve heard the concern—sometimes half-joking—that this removes a bit of Mormon “weirdness,” i.e., they enjoy the odd uniqueness of retaining the King James Bible over modern translations. But I don’t think the handbook change does anything to the peculiarity of Mormonism. Let’s be honest: there are no shortage of LDS distinctives left, e.g., embodied God, proxy baptism, Heavenly Mother. There are plenty of options to choose from. A readable Bible doesn’t magically erase uniquely LDS claims.

Also, encouraging modern English translations isn’t a gateway to evangelicalism. I’ve sense that concern, too, from some Latter-day Saints. Reading contemporary English translations isn’t a gateway to any Christian denomination; it’s a gateway to immediate, intuitive comprehension of the text. Besides, the Bible is half of the LDS canon. Why wouldn’t you want to read it rendered in language that can be readily understood?

#5 A Short Guide to the Recommended Translations

So, if you’re a Latter-day Saint wondering, “Which one should I read?” here’s my take.

First, none of the translations listed are perfect, nor can they ever be. No English Bible today is a flawless translation of the original texts, partly because we don’t have the original manuscripts themselves—though we can have a very high degree of confidence in their faithful transmission—but also because translation is an act of judgment. Moving meaning from Hebrew and Greek into English requires choices about vocabulary, syntax, idiom, emphasis, etc. Those choices are unavoidable.

That means every translation, including the KJV, reflects interpretive decisions, theological commitments, and practical priorities. The question isn’t whether interpretation is involved; it always is. The real question is whether those judgments are made carefully, transparently, and under the constraint of fidelity to what the text actually says.

In my opinion, the LDS Church has wisely recommended English translations that each reflect earnest translation judgements, who all share the same concern for both textual seriousness and readability.

On the more formal end are the NRSV and ESV. These stay closer to the structure of the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek while updating vocabulary and syntax. They’re especially useful for study, teaching, and comparison with the KJV. Of the two, I think the NRSV will feel most natural for most Latter-day Saints.

The NLT represents a more dynamic approach, prioritizing meaning in clear, contemporary English. It shines for readers who struggle with dense prose or who want the Bible to read smoothly without constant explanation.

The NIV sits comfortably between those approaches and often works well for sustained reading and family study.

The NKJV deserves separate mention. It retains the cadence of the KJV while removing many archaic turns of phrase. Basically, it’s great for readers attached to the sound of the KJV but not its opaqueness.

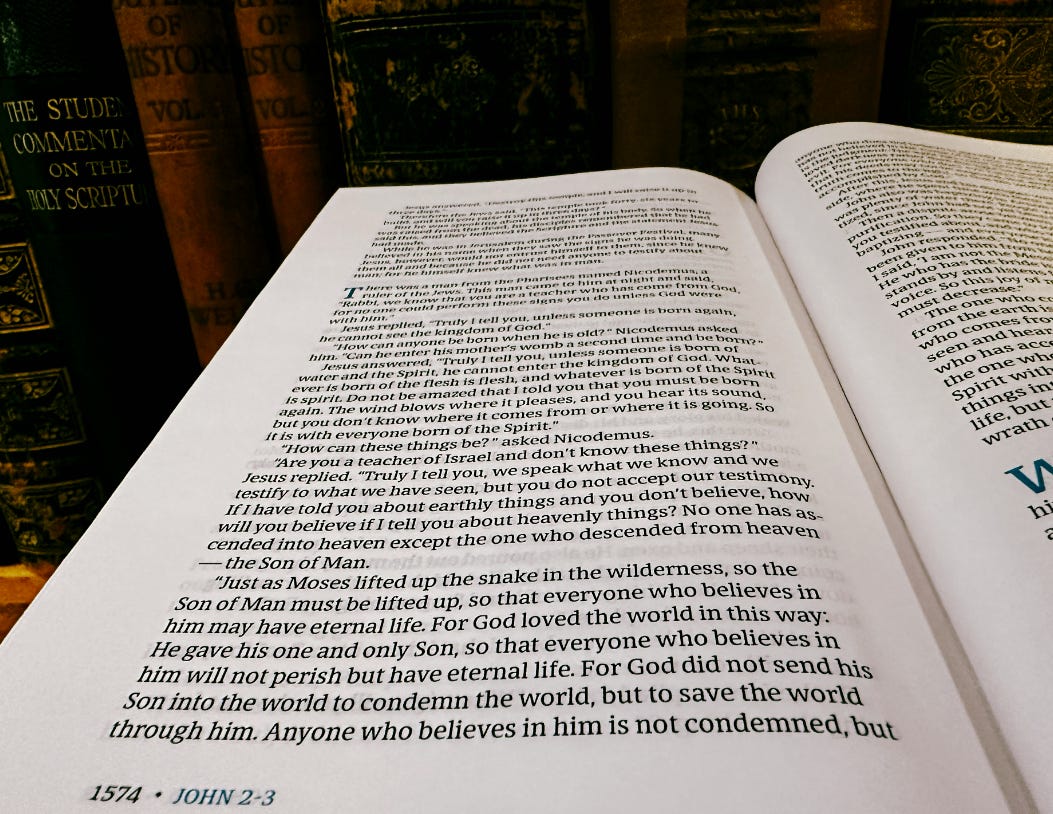

One of my favorites, the Christian Standard Bible (see above for John 2:19–3:18a), didn’t make the list, but I think it’s the best combination of a word-for-word and thought-for-thought translation. Highly recommended.

#6 A Small Word of Advice

Don’t turn Bible translations into tribal markers. This is among the least helpful things I see—and endure—as an evangelical pastor. Bible translations aren’t sports teams to whom you pledge lifelong allegiance and boo the rest from the stands. There aren’t really “good” vs. “bad” translations; there are more or less reliable translations.

In my experience, people with the strongest opinions about why this translation is the best—or why that translation is the worst—often lack basic familiarity with how translation works, or are fixated on a single disputed issue that has become a personal hobby horse, or just parrot their pastor’s or professor’s opinion, or were convinced by a meme online.

Don’t get caught up in that nonsense unless you plan to specialize in biblical linguistics, translation theory, and the long, technical arguments that professional translators and text critics trade in. That work matters, but for most of us—the overwhelming majority—there’s no obligation to contribute to the noise, repeat half-understood arguments, or defend a preferred translation as though the entire Christian faith depended on it.

Imagine Bible translations as players on the same sports team, each occupying a different position. The goal is the same—to ‘win’ by conveying meaning faithfully—but their strengths (‘positions on the field’) differ. One may excel at close textual work, another at clarity, another at narrative flow. Used together, they serve understanding rather than competing for loyalty.

#7 Let’s Get Practical

To see why consulting multiple English translations isn’t just permissible but actually helpful and wise, let’s slow down over a single, familiar verse.

James 1:5 is a fitting place to do that. It’s short, frequently quoted, super popular in the LDS world, and often memorized in the King James Version. Comparing how different translations handle it reveals what is gained—not lost—when clarity is allowed to do its work.

Jeff McCullough recently walked through this exercise on Hello Saints!, and it’s a good illustration of the basic method. We’re not trying to crown a winner here—remember, they’re all on the same team. Instead, the goal is to watch the Hebrew and Greek come into focus as they’re rendered through different English lenses.

The King James Version reads:

“If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him.”

For readers raised on the KJV, this sounds super familiar, even reassuring. For many modern readers, however, several phrases create friction.

“Lack wisdom” expresses absence, but not necessarily desire. I lack a thousand-dollar repair bill for a busted transmission, though I certainly don’t want one. James assumes that wisdom is a good to be desired, something the reader longs for, but that assumption isn’t explicit in contemporary English.

“All men liberally” poses a couple different problems. In modern usage, liberal usually signals political or social categories, not generosity. The older sense, “abundantly,” survives only as a secondary meaning. And also, the phrase “all men” can sound oddly restrictive: does God not give wisdom to women or children?

“Upbraideth not” presents the steepest hurdle. Be honest. You don’t know what that means instinctively. Most people either have to look it up or guess by context. The promise embedded in the verse—that God doesn’t scold, shame, or reproach the asker—sits behind a layer of linguistic opacity.

Now consider the New International Version:

“If any of you lacks wisdom, you should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to you.”

Here, several clarifications emerge.

“Gives generously to all” captures the force of the Greek pasin, which means simply “to all,” without narrowing the scope to men—in fact, the word for “men” isn’t even present in the Greek text to begin with. So, of course, women and children are also invited to pray for wisdom.

“Without finding fault” brings the emotional tone of the verse into view. God doesn’t blame you for your lack of wisdom. (Read that again; it’s important.) James 1:5 doesn’t tell you to come God sheepishly, hat-in-hand, to ask for wisdom because you’re too dumb to understand something. No! You just can’t see how the pieces fit together from your vantage point, but God can. So, you turned to God rather than the world for wisdom. Well done! That posture is commended, not corrected.

The New Living Translation presses this even further:

“If you need wisdom, ask our generous God, and he will give it to you. He will not rebuke you for asking.”

Notice the shift from “lack” to “need.” Wisdom is no longer framed as a mere absence but as a good the reader actively seeks. The translators also describe God as “generous.” That adjective doesn’t appear explicitly in the Greek, but the move is interpretive rather than reckless. A God who gives generously is, by implication, a generous God. The translation applies God’s action to God’s character, remaining well within the author’s likely intent.

Most striking is the final line: “He will not rebuke you for asking.” If the NIV brings us close to the heart of the promise, the NLT makes it unmistakable. God isn’t irritated by your request. He doesn’t sigh and roll his eyes and remind you that you should’ve known better by now. Asking for wisdom is not a moral failure; it’s an act of humble dependence.

With the KJV, NIV, and NLT side-by-side, James 1:5 takes on a more textured, meaningful form, doesn’t it?

Alright, that’s enough from me. If you’d like, I can revise this essay in Jacobean English to compare. ; )

📘 Coming February 2026: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

PRE-ORDER TODAY and download three free chapters while you wait.

As always, I enjoy reading from your perspective

Great article. I forwarded it to my wife and kids. A couple of weeks ago, my wife bought a copy of an ESV Bible. I poked at her a little bit over it, so when the Church made this change, she threw my teasing back at me. I haven't shopped for it yet, but I'd love to find a side-by-side version with the KJV and ERSV.

A few years ago, while doing some work in Kentucky, a friend invited me to join a small group meeting. It was among five Evangelical business owners who meet often to help each other with business decisions, review financials together, etc. They start each meeting with a brief scripture study and that day it was John 15.

I'm not sure which Bible version they were reading from, but I was following along on my trusty Gospel Library app, which is, of course, the KJV.

We got to verse 15 and whomever was reading used the word, "slaves", rather than "servants", and candidly, the wording was very jarring to me. The idea that Jesus would refer to the Twelve and His other disciples as "slaves" took me right out of the moment. When it was my turn to read, I actually went back to verse 15 first and commented on the difference.

I have not yet taken the time to go back and research how different translations treat John 15:15 and why other may have chosen the word "slave" over "servant", or which word is more correct. Eventually, I will because that memory surfaces every now and then and bothers me a little.

On the flip side, I personally always refer to the third member of the Godhead as the Holy Spirit. I think part of that came from living in the Bible Belt for so many years and having good conversations with my Evanglical friends, and I think that part of it comes from the modern view/definition of the word "Ghost" which I don't love. "Spirit" better captures who He is, in my opinion.