Joseph Smith’s Grandpa Wasn’t Actually a Universalist

At least, not the way we think of Universalism

Based on research for a forthcoming book.

I’d always heard Joseph Smith’s grandfather, Asael Smith, described as suspicious of organized religion, “avowedly Christian but basically irreligious.” I accepted this characterization for years, and perhaps you have, too.

So, I raised an eyebrow when I learned that this judgment rests almost entirely on a single, dramatic episode.

That realization sent me down a research trail I’ve only recently returned from, one that forced me to revise my understanding of Joseph Smith’s paternal grandfather.

I don’t think Asael Smith was a “irreligious” Universalist.

Instead, I think Asael Smith is better understood (by today’s terminology) as an Inclusivist with universal hopes, and a very religious one at that.

So, why do people think he was ‘irreligious’? Two primary reasons, I think:

Asael apparently liked Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason and was hostile to organized religion.

Asael founded a Universalist society in Vermont.

At face value, sure, it looks like Asael was no fan of the Christian orthodoxy. But that’s only because we lack context and we project our contemporary theological definitions onto Asael.

I found that the closer you step toward Asael, the more apparent his inclusivism becomes.

First up, Asael’s infamous Age of Reason episode.

Hurling Reason At Joseph Smith’s Dad

In 1803, Asael visited his son, Joseph Smith Sr., and daughter-in-law, Lucy, after learning they’d started attending Methodist meetings. According to Lucy’s later recollection, her father-in-law reacted with fury. He reportedly stormed into their home, hurled a copy of The Age of Reason toward Joseph Sr., and “angrily bade him to read that until he believed it.”

Admittedly, that looks like Asael was a cage-stage Reddit atheist. From that moment alone, it’s easy to imagine Asael as a disciple of Thomas Paine, hostile to Christianity itself, and eager to replace faith with reason.

That conclusion, however, asks way too much of this single episode, as other evidence shows. As Richard Lloyd Anderson cautioned long ago, there’s little reason to assume Asael embraced Paine wholesale, especially the skeptic’s ridicule of Christ’s atoning work. The incident clearly reveals opposition, but the object of that opposition is what interests me.

What Asael rejected wasn’t Christ, but a form of Christianity that, in his judgment, distorted Christ’s work and burdened the conscience (more on that later). Asael appears to have favored Paine’s appeal to reason as a weapon against clerical coercion, not as a substitute for the gospel. In other words, Asael plundered Egypt: he took Paine’s rational tools but not his theological conclusions.

But what about his Universalism?

The Vermont “Rural Intelligensia”

Asael was raised a Congregationalist (Calvinist) but later became a founding member of an Universalist Society (definitely not Calvinist) in Vermont in the late 1790s, several years before the book-throwing episode.

So, he’s squarely in the Universalist camp, believing all religious roads lead to heaven regardless of the path to get there, right?

Wrong.

Early American Universalism wasn’t like the religiously pluralistic Unitarian Universalism we’re familiar with today. Nor was it a refuge for the religiously indifferent. It attracted women and men who were intensely moral, biblically literate, and theologically engaged, yet deeply suspicious of traditional creeds and church authority. Randolph Roth aptly described Vermont’s Universalists as members of the “rural intelligentsia,” self-taught farmers and artisans whose theological instincts rubbed against the grain of established churches.

Asael fits that description neatly.

His resistance wasn’t to Christianity itself but to institutionalized Christianity. In particular, it was Calvinism’s doctrine of election and Methodism’s insistence on repentance as the necessary escape from eternal conscious torment that appears to have struck him as morally objectionable.

Asael wasn’t “irreligious;” his was an anti-institutional, reason-based Christian piety.

That posture becomes extremely apparent in a letter he later wrote to his children in 1799. In it, he didn’t commend skepticism or moral autonomy. Rather, he urged them repeatedly toward “the scriptures” and “sound reason,” calling these the two “witnesses” God had appointed for learning the gospel, not creeds and clergy.

Within this framework, Asael asked a pressing question: Did salvation consist in “outward forms, rites and ordinances,” or did sinners require help “from any other hand than [their] own,” i.e., a pastor or priest? No. The issue wasn’t whether Christ saves, but how salvation is secured and received.

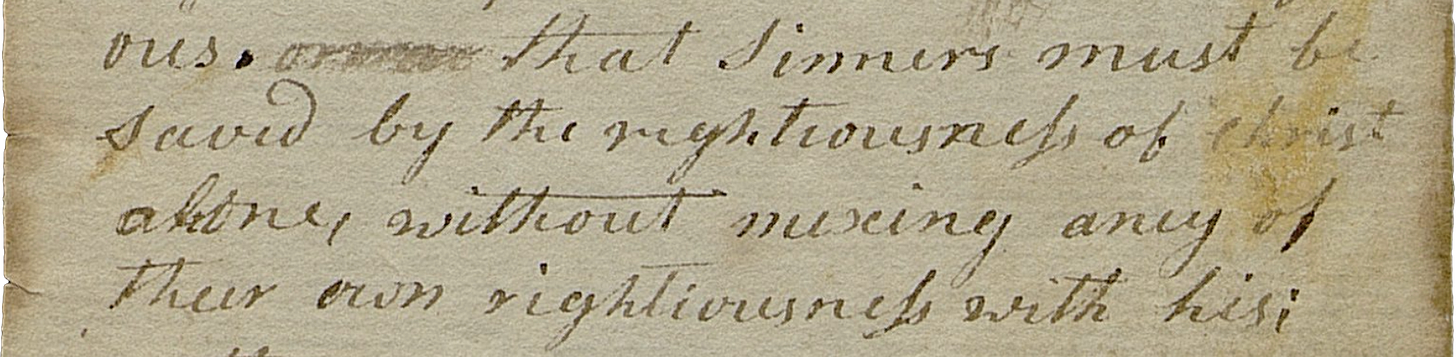

And this is how Asael understand it: “Sinners must be saved by the rightiousness of Christ alone, without [mixing] any of their own rightiousness with his.”

Amen, Asael.

Now, that might surprise some readers, given Asael’s reputation as an “irreligious” Universalist, but this is why history matters.

Early American Universalism never denied Christ’s uniqueness in redemption; rather, it argued for its widest scope possible—all people everywhere—via the most narrow, exclusive mechanism possible—Christ’s cross alone, e.g., not deism, not Islam, not paganism, etc.

And we see that reflected in Asael’s letter. He didn’t believe there were multiple paths to heaven. He universalized the reach of Christ’s atonement, not the method. Christ’s work was sufficient, complete, and impartial, extending to all rather than restricted to a predestined few. Certainly, no one should be coerced by a preacher into begging God for salvation at a Methodist camp meeting; they need to realize God already has saved them. God showed no partiality whatsoever, which was an Asael held a universalist hope that God “can as well save all as any, and there is no respect of persons with God.” God can save all, said Asael, and “will have all mankind to be saved” (i.e., God desires that all humanity are saved), not through myriad religious paths, but through Christ alone because, according to Asael, “there is one God, and one mediator between God and man” (see 1 Timothy 2:5). Again, neither the gods nor Muhammad are the mediators here: it’s Christ alone.

So, in contemporary theological terms, I think Asael’s position aligns most closely with a sort of ‘universal-hoped Inclusivism,’ i.e., the conviction that salvation is accomplished exclusively through Christ, yet applied by God beyond the boundaries of explicit knowledge or institutional affiliation, so as to include more people than we might suppose, and hopefully all people in the end.

In that sense, Asael stands closer to figures like C. S. Lewis (The Last Battle) or David Bentley Hart (That All Shall Be Saved), both of whom frame salvation within a Christological account—Lewis inclusively and Hart universally. Neither Lewis nor Hart (nor Asael) believe in a sort of diffused, relativistic salvation like the (Unitarian) Universalism we know today, which functions less as a Christian soteriology than as a generalized moral intuition.

I’ll go so far as to say this: Early American Universalists, like Asael, would have regarded contemporary Christ-less Universalism as incoherent nonsense, perhaps even heretical.

Now, just to clarify, I’m not a universalist. I can’t get around Christ’s stark warnings about wide gates that lead to “destruction” (Matthew 7:13), that God can “destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matthew 10:28), that the fruitless are pruned and destroyed (see John 15:6), and that many will hear “I never knew you; depart from me” (Matthew 7:23). This all suggests a definitive, irreversible exclusion from eternal life rather than its universal bestowal. I land where Lewis did: In the end, someone has to say, “Thy will be done,” whether it’s us or God. Eternal death and destruction are real, and if anyone is there, it’s because they chose it.

(This essay isn’t about me, it’s about Asael, but I just wanted to clarify.)

Was Asael Smith Really “Irreligious”?

So, was Asael Smith “avowedly Christian but basically irreligious”? Only if one assumes that distrust of established churches amounts to disbelief in salvation itself. In reality, Asael’s soteriology was centered on the conviction that Christ’s exclusive atonement extended to all humanity. It rested solely on Christ’s completed work but on a mode of atonement—an infinite one—that traditional Christianity didn’t teach him.

This is interesting to me because it presages later Mormon soteriology. Asael’s Universalism may have suppled the Smith family the soteriological ideas and grammar in which later Mormon expansion became not only possible but coherent within its own system. A salvation already extended to all humanity through Christ—his infinite atonement efficient to resurrect all—would require a heavenly cosmos spacious enough to receive it, though fair enough to reward human efforts (or lack thereof).

That’s why D&C 76 doesn’t register as a theological rupture to me. Out of step with traditional Christianity, yes of course, but not unpredictable or incoherent in Mormon thought. Joseph Smith didn’t replace a narrow heaven with a wider one. He organized a heaven already presumed to be wide, because that’s what he grew up with. Degrees of glory distribute the effects of Christ’s atonement rather than diminish them, at least as Joseph understood the matter.

Ok, so, here’s where I land now: Asael Smith wasn’t “irreligious,” but he was convinced that salvation outran orthodox limits, but always and forever ran through Christ.

Asael Smith was’t religious pluralist, which is how we typically understand Universalism. In contemporary terms, Asael was a believing Inclusivist with universalist hopes.

Read Asael Smith’s 1799 letter here.

📘 Coming February 2026: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

PRE-ORDER TODAY and download three free chapters while you wait.

Love this article in so many ways. People are complex and the more we get the truth about them, the better.

This is great and I think applies to a lot of thinkers from that age, including many of the Founding Fathers. It’s easy to confuse unorthodoxy with deism or rejection of Christianity. I recently had a conversation with someone about John Quincy Adams, for example. He is quoted as doubting the “divinity” of Christ, but believed in Christ as Redeemer, studied the Bible devotedly, believed in life after death, etc. His questioning the “divinity” of Christ really meant questioning the nature of the Trinity, not whether He was more than man. It would be a mistake not to consider him Christian.