What Constitutes Evangelical Anti-Mormonism?

On the Spectrum of Evangelical Engagement with Latter-day Saints

Note: Thanks to everyone who subscribed after my last essay. It spread farther than I expected. For those new, this Substack is mainly an irenic evangelical look at LDS history, faith, and practice. It’s not typically about current events, so if that’s not what you’re into, no worries. Feel free to unsubscribe and keep your inbox clean.

I recently wrote about evangelical reactions to the tragic murders in Michigan and the kind of rhetoric that too often fuels contempt for Latter-day Saints. Since then, I’ve gotten a lot of questions—mostly from evangelicals—about what I see as the difference between anti-Mormonism and honest (though polemical) engagement with Latter-day Saints.

It’s a good question, especially because it touches on so many others. Is street preaching in downtown Provo or outside General Conference anti-Mormon? Is it anti-Mormon to say “Joseph Smith was a false prophet?”

As an evangelical pastor, I’ve fielded plenty of practical questions over the years: What should I say when LDS missionaries come to the door? How direct should I be? How do I hold my convictions without being rude? Those are good questions, but behind all of them, I keep circling back to a deeper one. At what point does honest disagreement cross the line into anti-Mormonism?

Let me lay my cards down early: I believe evangelicals should be able to say, without being accused of malice, what we believe and why. We don’t believe Joseph Smith was a prophet or that the Book of Mormon is scripture or that the gospel was restored after a Great Apostasy. I don’t call it the Restoration out of personal conviction. I mean, it’s obvious we don’t believe LDS truth claims, isn’t it? If we did believe those things, we’d be Latter-day Saints. So, those statements are convictions, not contempt. They aren’t anti-Mormonism. Contra-Mormonism, sure, but not anti.

But there are ways of expressing those convictions that cross a line into something else entirely, ways that mock, misrepresent, or dehumanize. And that line has been crossed very publicly recently. There’s a difference between clarity and cruelty, and losing that distinction is where anti-Mormonism begins.

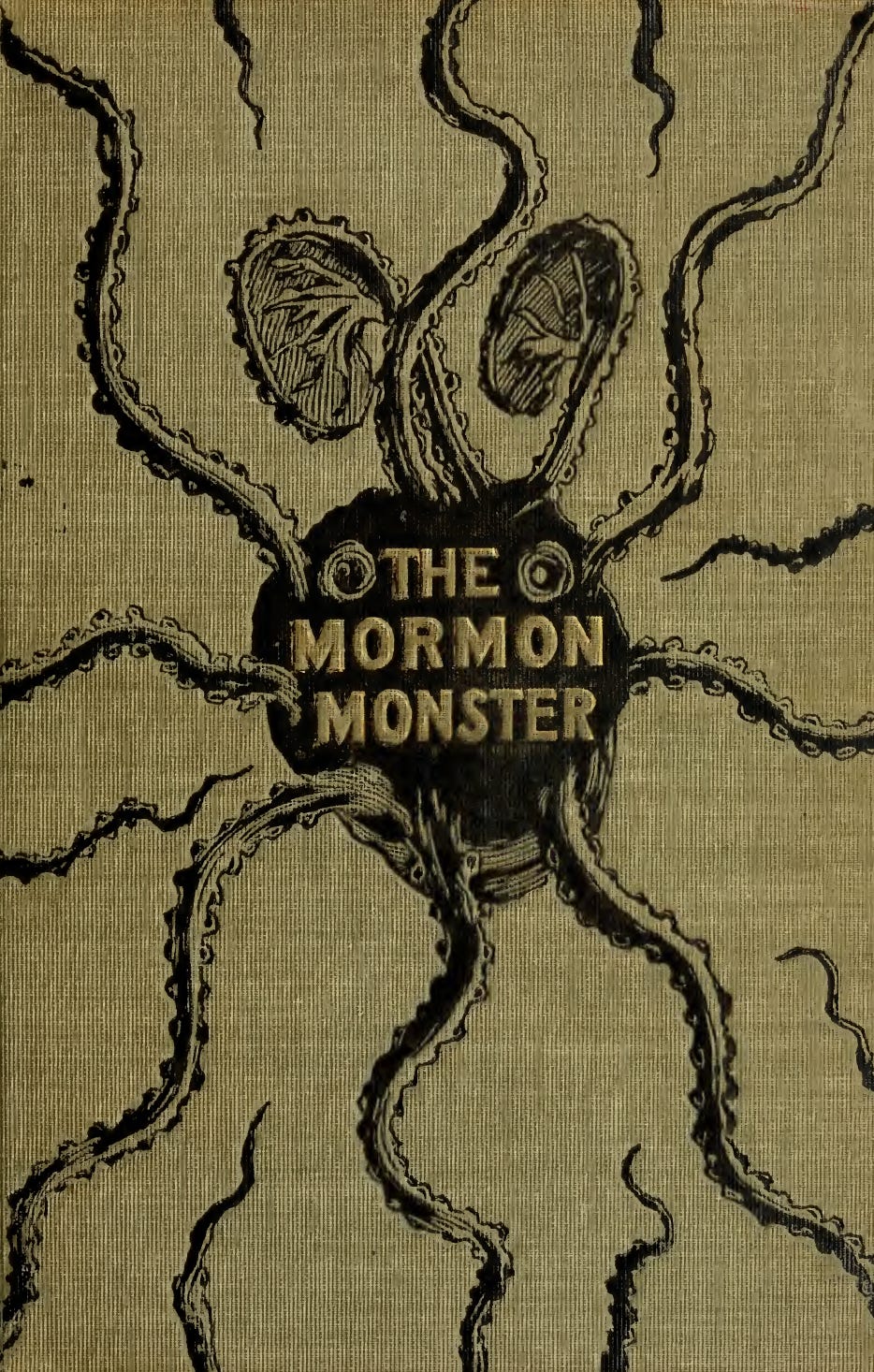

Sometimes it takes the form of false witness, framing things in a way that simply isn’t true, like when someone says, “Mormons worship Joseph Smith above Jesus Christ.” (The Michigan murderer was, allegedly, convinced the LDS Church was anti-Christ.) Sometimes it turns into sensationalizing, like stretching doctrine into crude or lurid caricature, as in, “Mormons believe Elohim had sex with Mary to conceive Jesus,” e.g., The God Makers. Other times it reduces to a lazy mischaracterization, a sort of half-joke, half-sneer that says, “All Mormons think they’ll get their own planet and a harem of wives to populate it when they die.”

These statements aren’t accurate, let alone entirely fair or charitable. Any truth in them is distorted beyond recognition, curated at the most sensational edge, stripped of context, and presented in a way meant to scandalize. Their purpose isn’t to clarify but to shock, to instill fear, and, in some hearts, that fear hardens into anger. (I’ve written on this, too.)

Now, to be clear, I think evangelicals ought to discuss our distinctives in contrast to Mormonism. By ignoring those convictions altogether, we risk falling into a shallow niceness that mistakes silence for love. If we don’t ever talk about our differences, we won’t truly know one another, only polite, synthetic versions of ourselves.

So, what “modes” of engagement exist between anti-Mormonism and conviction-less, syncretistic silence?

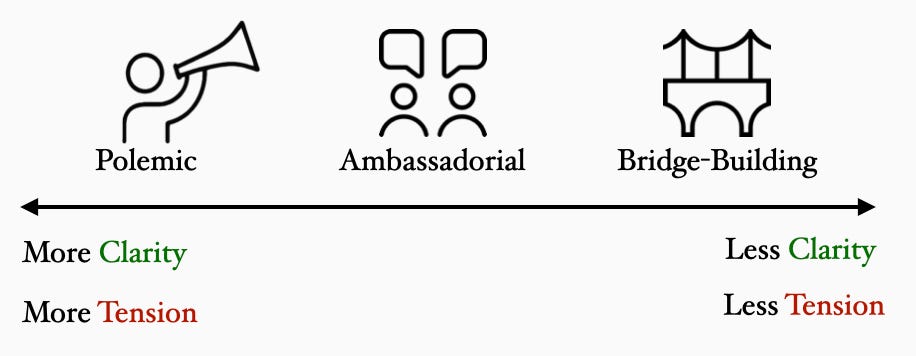

Inspired by conversations with friends, I’ve sketched out a kind of spectrum—different modes of evangelical engagement with Latter-day Saints. This isn’t a prescriptive model so much as a descriptive one. I’m not telling anyone what to do, apart from my cautions about anti-Mormonism and syncretism. What follows is simply the landscape as I’ve observed it—unfinished, still forming, but, I hope, recognizable to anyone who has spent time in this space.

(Just a quick aside before moving on. I wrote this essay primarily with evangelicals in mind, although I’m very aware of Latter-day Saints reading over my shoulder. If that’s you, I welcome it. My hope is that you hear not hostility but honesty, and that even where we disagree, you sense a desire for clarity with charity.)

The Three Modes of Evangelical Engagement

First is The Polemicist Mode, an apologetics-based, evangelistic-minded approach.

This is perhaps what evangelicals are most known for. It’s certainly the primary mode. As a missional movement, evangelicals are driven to evangelize, thus the name. The Polemicist Mode directly names differences and defends evangelical distinctives. It’s typically a one-way street, but doesn’t always have to be. In fact, conversational polemics have grown more popular over the years. At its best, it can be sharp but not cruel, aiming for persuasion rather than humiliation.

Think of street preaching and conversations on the sidewalk behind “Change My Mind” posters, or the work of evangelical apologetics organizations. Done rightly, this mode creates opportunities for evangelicals to express truth from their perspective clearly while still treating the Other with dignity. I think organizations like Mormonism Research Ministry and YouTube channels like God Loves Mormons are prime examples.

Rhetoricians operate differently than I tend to, but I appreciate that they’re at least engaging rather than ignoring. It’s a sign that they genuinely care, and as strange as that sounds to Latter-day Saints, some evangelicals actually do sincerely love Latter-day Saints and express that love by showing up and speaking what they believe is true.

That said, I’m admittedly a bit wary of what I consider a cottage industry of how-to resources that has grown within polemic evangelical engagement with Mormonism. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not opposed to people reading them. I just know from experience that if our understanding of Latter-day Saint faith and practice is mediated almost entirely through comparative guides (even good ones), we end up analyzing the Other rather than knowing our neighbor. It starts to feel like learning a foreign language only well enough to order food and ask for directions, rather than learning it to actually know and be known by the people who speak it. That difference—between functional vocabulary and relational fluency—is a serious one.

And it’s super weird to think about ‘how-to’ resources in reverse, e.g., Introducing the Restoration to Evangelicals: A Practical and Comparative Guide to What the Prophets Teach or Responding to the Evangelical Missionary Message: Confident Conversations with Evangelical Preachers (and Other Traditional Christians). I’m not sure how many Latter-day Saints would find that approach genuinely illuminating, and they’d probably be picked to the bones by evangelical apologists. For what it’s worth, I’ve found more light in lived accounts—like Lynn Wilder’s Unveiling Grace—than in step-by-step rebuttal manuals.

Second, there’s The Ambassadorial Mode, the relational, representative approach.

This mode is less about public argument and more about public presence. Ambassadors seek to represent evangelicalism with clarity and kindness, building trust across difference. They still name disagreements, but they do so in the context of hospitality and friendship. If the polemicist is aiming to persuade the mind, the ambassador is aiming to open the heart.

You can see this in things like YouTube channels such as Hello Saints! with Jeff McCullough, or evangelicals (especially in the Mormon Corridor) who invest years in neighborly dialogue with Latter-day Saints. I consider my forthcoming 40 Questions About Mormonism to be done in this mode, i.e., an exploration of the LDS Church that seeks to understand, not just refute.

But even here, there are trade-offs. The Ambassadorial Mode runs the risk of softening the edges of conviction in the name of kindness. Ambassadors can sometimes feel pressure to maintain the relationship at all costs, and in doing so, clarity can begin to blur, not maliciously, but gradually, through the slow drip of conflict-avoidance. I’ve certainly felt this. When hospitality becomes silence, the posture that began as charity can quietly drift toward ambiguity. And once that line blurs, it becomes difficult to recover clarity without feeling like you’re breaking the peace you worked so hard to build.

Then, there’s The Bridge-Building Mode, a dialogical, cooperative approach.

Here, the aim is less immediate persuasion and more long-term understanding. Bridge-builders look for common ground where evangelicals and Latter-day Saints can walk together, e.g., shared moral concerns, community service, honest theological dialogue. They recognize the importance of clarity, but they lean heavily on charity.

Examples include ministries like Standing Together, which tilled the soil in which the Mouw–Millet dialogues grew. I love Standing Together, and have supported it annually (for over a decade now), and am personally a beneficiary of it. I’ll admit, I was initially hesitant about this mode. Early on, I wondered if it blurred the line between understanding and endorsement, especially when I saw how warmly some evangelicals spoke of Latter-day Saint leaders. But the more I watched the ministry’s leader, Greg Johnson—whom I deeply respect—the more I came to appreciate the wisdom in what he’s built through Standing Together.

Now, I don’t consider these modes to be concrete categories assigned to rigid personality types. They’re more like assignments we take up depending on calling, context, or circumstance. Evangelicals can (and often do) oscillate between them. A person might take a polemicist stance with a lively LDS interlocutor, act as an ambassador over lunch the next day, and step into bridge-building at a community forum later on. But while there’s movement, most of us tend to camp out in one of these spots more often than the others.

For me, the Ambassadorial Mode feels most like home. That’s where you’ll find me 90% of the time, anyway. Bridge-building is a close second, and only rarely (usually in response to bellicose LDS apologists) will you find me stepping into the Polemicist Mode.

Why prefer one mode over the other? The answer depends on what you’re willing to trade off, and it’s important to name them honestly.

The Polemicist Mode is strongest on clarity. It leaves little room for misunderstanding where evangelicals (in aggregate) stand. But clarity comes at a cost: it often creates tension, and when handled poorly, that tension can sour into hostility. In it’s worst form, it slips into anti-Mormonism (more on that below).

The Ambassadorial Mode strikes a careful balance. It maintains clarity while lowering tension, since disagreements are couched in trust and relationship. But even here there’s a trade-off. Sometimes the concern to be gracious can soften convictions to the point that clarity feels muted.

The Bridge-Building Mode excels at reducing tension. It models respect, charity, and peace. Yet, the risk is that clarity can get lost in the pursuit of common ground. And if clarity evaporates entirely, what remains is little more than cordial coexistence, not true dialogue. In its worst form, it slips into syncretism, i.e., blending evangelical and Latter-day Saint convictions in a way that blurs or even erases the real differences between them, and does disservice to both sides.

So, in one sense, evangelicals face a spectrum: the further we move toward clarity, the greater the tension; the further we move toward reducing tension, the greater the risk of losing clarity. Neither end is “wrong” in itself, but both come with dangers we should be aware of.

Let’s talk about those dangers.

Twin Opposite Pitfalls

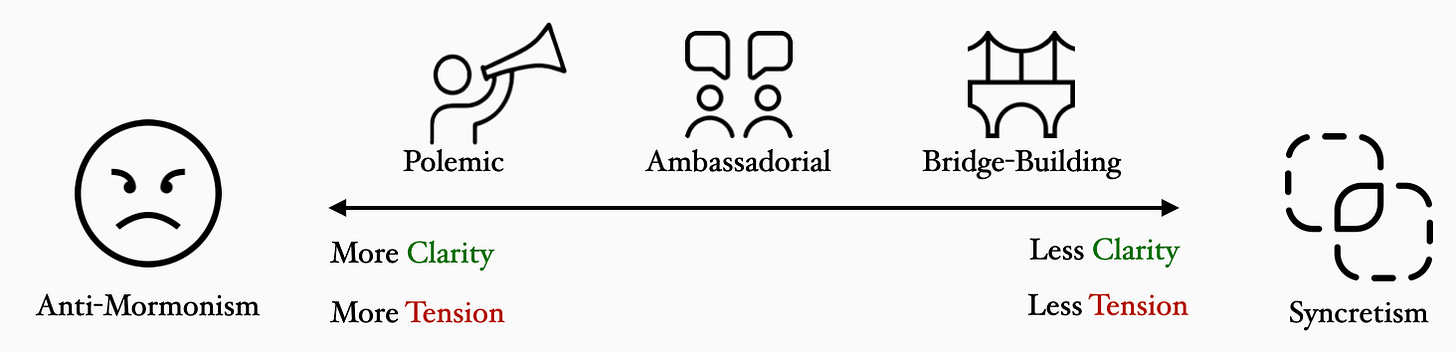

I consider the following modes of evangelical engagement pitfalls to avoid at all costs: syncretism and anti-Mormonism.

First, syncretism. This is the blurring of convictions to the point that the real and serious differences between evangelical and Latter-day Saint faith are minimized or erased. It’s when the desire for peace and goodwill leads us to pretend we believe the same gospel when, in fact, we don’t. Let’s be real—differences of spiritual authority, doctrine, and practice create insurmountable obstacles to overcome. It’s okay to see them, name them, and discuss them, but let’s never pretend like they don’t exists. That’s just disingenuous. It may feel charitable in the moment to ignore differences, but it ultimately withholds truth, and withholding truth is not love.

Second, anti-Mormonism. This is the opposite error: seeing and naming differences, and then mocking, misrepresenting, or dehumanizing Latter-day Saints. It’s contempt masquerading as conviction, and can even lead to violence. It thrives on caricature and ridicule. It bears false witness against our neighbors.

You’ve seen it all before: memes that treat the Book of Mormon as toilet paper; sermons that make Latter-day Saints the punchline of a joke; online rants that brand every LDS temple as “demonic.”

One particularly egregious example was brought to my attention: a comment by an evangelical (I hesitate even to give him that title) who said,

“Gods going to burn every single Mormon in eternal hellfire. Back in the day we used to be able to get them there faster. Shame we can’t anymore.”

Let me be clear. This isn’t just anti-Mormonism; it’s sin. It’s evil, sociopathic slander that needs to be repented of. Who laments the inability to send anyone to hell faster? It’s sick.

But notice that critiquing Mormonism isn’t the same as being anti-Mormon. It’s possible—indeed necessary—for evangelicals to critically engage with Latter-day Saint history, beliefs, and practices without crossing that line. It isn’t hateful to say that Joseph Smith wasn’t a prophet or that the Book of Mormon isn’t scripture. I believe those things, and I say them regularly when clarifying my convictions. But there are certainly hateful ways to say them. Calling him “ol’ Joe” and reducing the Book of Mormon to demonically-inspired toilet paper, for instance, is not only unhelpful, it’s stupid.

In fact, over the years, I’ve come to the conviction that quality critical engagement with Latter-day Saints is actually evidence of respect. Evangelicals who dedicate time and energy to understanding Mormonism aren’t motivated by contempt, but by the conviction that truth matters and people matter. But because most evangelicals don’t think about Latter-day Saints at all, there’s a sort of asymmetry in the relationship. Latter-day Saints are used to being discussed, analyzed, and missionized. Evangelicals aren’t. So, when a small number of us do step into that space, we need to remember: (1) we are de facto representatives of evangelicalism, whether we like it or not, (2) we’re late to a conversation others have been having about us for generations, and (3) because of that, we enter with a deficit of awareness, not a surplus of authority. I think that should make us slower to speak and quicker to listen.

And if you can’t get there, then don’t, because there’s a deeper point here. If we can’t get the ABCs of the gospel right, we have no business pretending we’re ready for the advanced things. The ABCs are clear enough. Jesus said, “Love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength” (Matt. 22:37–38; Deut. 6:5), and, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Matt. 22:39; Lev. 19:18). The entire Law hangs on these two commands. Add to that the Golden Rule, “Do to others what you would have them do to you” (Matt. 7:12), and the “new commandment” He gave His disciples, “Love one another, just as I have loved you” (John 13:34).

If we ignore these basics while rushing headlong to debate the nature of God, the authority of scripture, or questions of salvation, heaven, and hell, then we’ve missed the order of things. The foundation of gospel engagement is love. Without that, whatever else we build will be crooked.

That’s why I can’t stand anti-Mormonism.

It’s genuinely love-less.

Dr. Iscoll and the Woman of Samaria

So, how can evangelicals avoid anti-Mormonism and syncretism? There are myriad examples in the Bible, but my favorite is Jesus’s encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well.

In John 4, when He met her there, Jesus didn’t belittle her, mock her Samaritan scriptures, or ridicule her Samaritan temple. He discussed truth with clarity, yes, but He did so while offering living water.

(I realize that Latter-day Saints may bristle at this analogy because it assumes evangelical Christianity as the wellspring of truth, but bear with me. My point isn’t to exalt one side and demean the other. My point is to show the stark difference between contemptuous rhetoric and Christlike engagement.)

To understand this point, I’ll end with a remix of the Woman at the Well passage with the bellicose, anti-Mormon rhetoric of, say, a famous evangelical named Dr. Iscoll.

Now when Dr. Iscoll had wearied himself with the journey, he sat down beside Jacob’s well. It was about the sixth hour.

There came a woman of Samaria to draw water, and Dr. Iscoll said to her, “Give me a drink.”

The Samaritan woman said to him, “How is it that thou, a Jew, askest a drink of me, a woman of Samaria?” For Jews have no dealings with Samaritans.

Dr. Iscoll answered her, “Thy scriptures are fit only to hold open doors and to serve as refuse; thy temple is the haunt of demons; and verily, not one Samaritan shall enter the Kingdom of Heaven.”

The woman said to him, “Sir, I perceive that thou art a prophet of wrath and not of mercy. Our fathers worshiped on this mountain, and ye say that in Jerusalem is the place where men ought to worship. But dost thou bring no good tidings, save curses?”

Dr. Iscoll said to her, “I tell thee the truth: every Samaritan shall perish in hell, for none of thy people shall in nowise enter the Kingdom of God.”

The woman left the well, and said within herself, “Surely this man bringeth no living water, but bitterness. I will not tell the city of him, save to warn against him and his disciples, for his words are hard, and there is no hope in them.”

And thus the well was silent, and no harvest was gathered in that place.

So What?

This remix shows what happens when anti-Mormon rhetoric replaces witness. There’s no good news left, only bitterness. There’s no invitation to life, only condemnation. And if our words drive people away from the living water of Christ, then we are not evangelizing, we are vandalizing the gospel.

So, let me close with this: evangelicals, we’re not called to mock. We’re not called to caricature. We’re not called to treat our neighbors as if they were less than human. We are called to bear faithful witness to Jesus Christ—who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life—by speaking the truth in love. That means holding our convictions without cruelty and showing compassion without compromise.

If we can’t get the basics right—to love God and to love our neighbors as ourselves—then we have no business pretending we’re ready for the advanced things of the gospel.

Be clear with your convictions, but let it always be tempered by charity. Build bridges where you can, speak honestly when you feel that you must, but let everything you say and do be marked by the Spirit of the Lord Jesus.

📘 Coming February 2026: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

I came to write a different comment, and ended up writing an essay in response to Drew. Ugh. That got me worked up.

I've been pondering this essay on and off since I read it and want to share a personal example of how, if virulent anti-Mormonism were to spread in the way that Dr. Iscoll would like it to spread, lives would be affected:

For a period of about 10 years, I worked in the film industry from my desk in Oklahoma City. First for LD Entertainment which was based in Hollywood and Oklahoma City. Next for the Erwin Brothers/Kingdom Story Company, which was based originally in Birmingham, AL and later moved to Franklin, TN.

I was hired by the founders of LD Entertainment after they had to remove the prior VP of Finance. The partner who interviewed me specifically noted my attendance at BYU's Marriott School and began asking questions that his HR department would have hated. I'm not saying that I was hired BECAUSE I was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but after our meeting, he had a pretty good idea of my morals and standards, and it didn't hurt.

If Dr. Iscoll had his way, I'd have been immediately dismissed from the interview for being a demon and worshipping demons.

From that hire, I've been able to work on films like "Risen", "I Can Only Imagine", "Jesus Music", "Jesus Revolution", "I Still Believe" and more. I've rubbed shoulders with many Evangelicals. I've been pointed to as the token "Mormon" in meetings. I helped the Erwin Brothers with their rebrand to Kingdom Story Company and assisted with the move to Tennessee so they'd have more access to amazing creative talents.

For my part those were amazing opportunities and I loved (and still love) my Evangelical brothers and sisters who write, produce, create, edit, and market films like these that our culture desperately needs.

All those opportunities would have vanished from my life if anti-Mormonism had become mainstream by the 2010s. Those groups may have found someone else to do the work that I did - I'm sure they would have - but I like to think that I added to their lives as well.

I hope and pray Baptists, Methodists, Non-denominational Christians, and other Evangelical groups AND Mormons find ways to break down more walls and work together, rather than raising more walls.

I know your Substack is not specifically for combating anti-Mormonism, but I am enjoying it and I am grateful for your two most recent essays on that topic in any case.

Great read, really liked you taking the woman at the well experience and translating modern discord into prior scriptural discourse.