This Is the Place, But Not Yours

The Territorial Legacy Behind Utah's Public Land Debate

When Utah Senator Mike Lee inserted a provision into the “big, beautiful bill” that would’ve let the federal government sell off millions of acres of public land—mostly in the West—it triggered bipartisan backlash. Critics called it a land grab that threatened conservation and access to some of the nation’s most beautiful land.

Lee eventually backed down.

Presently, in Utah alone, about 37.4 million acres (~68%) are federally managed. For perspective, that’s a chunk of Utah roughly the size of Florida.

Much of that land is open to the public, like the many national parks. Other land is closed for military use, like the Dugway Proving Ground (itself the size of Rhode Island).

Why does the federal government own so much of Utah? you might wonder.

The answer, as with much in Utah, is tied to its Mormon roots.

The Dream of Deseret

In 1849, the Latter-day Saints asked Congress to recognize a new state they called “Deseret.” It would have been the 31st in the Union, but after Congress said “no,” California beat them to it in 1850. Meanwhile, Utah—the much smaller slice of what Deseret once claimed—wouldn’t become a state for another four decades (1896).

“Deseret,” a Book of Mormon term meaning “honeybee,” reflected how the Saints saw themselves: industrious and cooperative, working together to build a new society in what most Americans saw as an unforgiving, God-forsaken desert. (Of course, this perception belonged to the Euro-American settler type used to the lush forest in the east; to the indigenous, like the Utes and Paiutes and Shoshone, the land was anything but desolate.)

Anyway, the Mormons had begun settling the Great Basin just a few years earlier, fleeing persecution in Illinois and Missouri. When Brigham Young first entered the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847, he reportedly declared, “This is the place,” and directed waves of colonization throughout the area. With irrigation and communal labor, they turned desert into farmland and called it home.

But for the federal government, the place may have been Utah, but it wasn’t theirs. Not politically, not legally, and certainly not in the way the Saints envisioned.

So when Church leaders pushed for statehood, Congress balked. A Mormon-led state, stretching from the Rockies to the Pacific, would have split the continent and given the LDS Church enormous regional power. The Saints’ practice of polygamy didn’t help either. For many in Congress, it confirmed suspicions that Deseret would be a theocracy, not a state.

Deseret was denied and the dream of the Mormon state died.

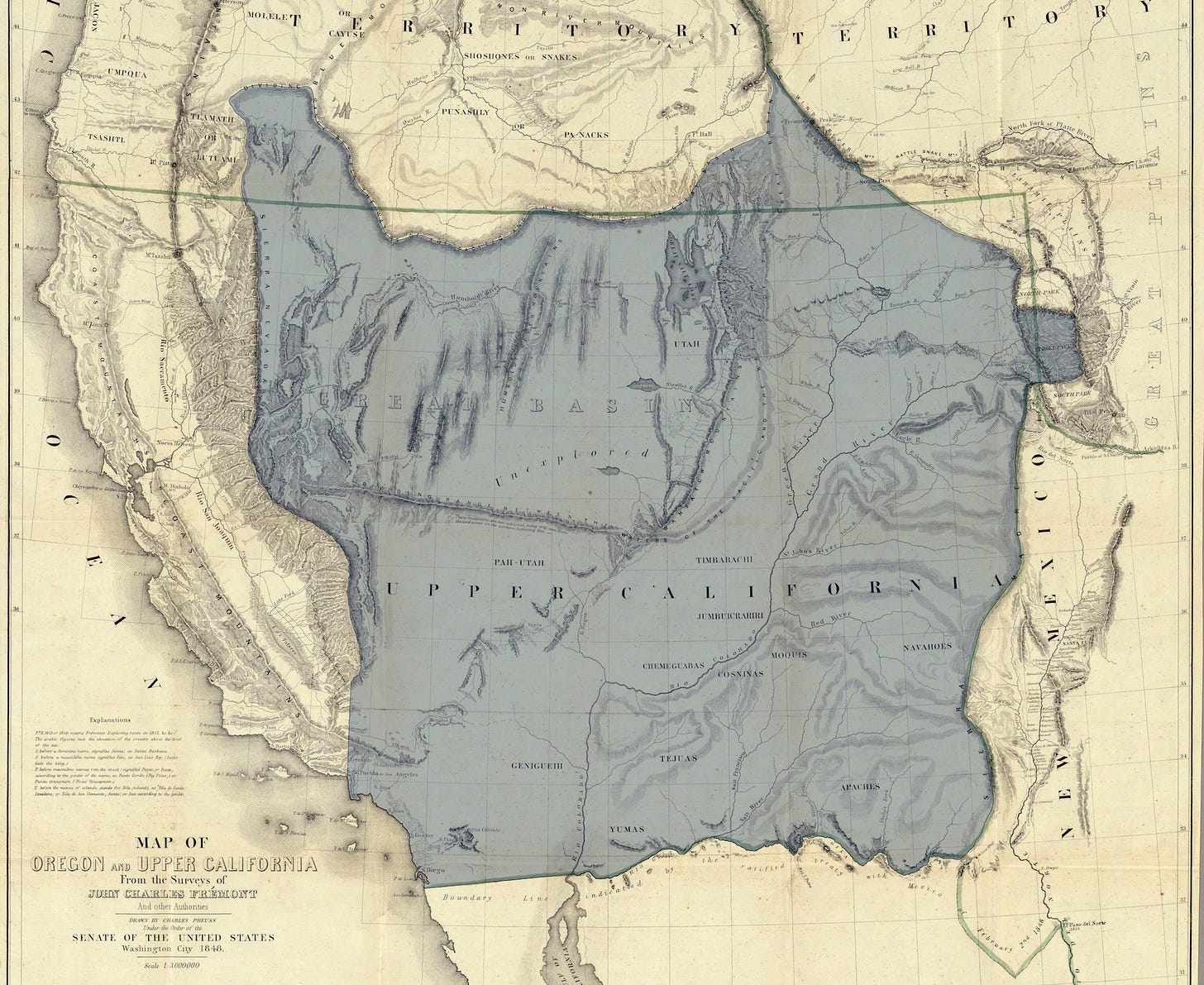

Here’s a map I made of what the Mormons proposed, based on the same 1848 Charles Preuss map LDS leaders likely used to draw its boundaries (now housed in the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection).

They followed watershed boundaries. If it didn’t drain to the Columbia or the Gulf, it was Deseret. They included San Diego to secure a Pacific port and tried to split the Sierra Nevadas, giving Saints access to the gold rush—and gold-rushers access to Mormon supply chains.

Fun fact: there are only three straight lines. Two are in the southwest corner, which most folks know about, but can you find the third? (You’ll probably need the hi-res version to find it. See below.)

The result? A state that looks like someone tried to draw France from memory. But behind the odd shape was a serious vision: a self-governed Mormon commonwealth stretching across the West.

Until Congress denied it.

Download a hi-res version [here]. (Feel free to use it, just please give credit. It took my a long time to make.)

Why does all this matter now?

Because the land still tells the story. After rejecting Deseret, the federal government established a military fort near Salt Lake City (Fort Douglas, 1862). While officially intended to protect overland mail routes during the Civil War, its strategic positioning also served as a visible federal presence in the Mormon heartland. The also government eventually built the capitol on a hill high above the Salt Lake Temple (completed 1916). Whether symbolic or simply practical, the message was clear enough.

Washington was in charge.

Of course, federal retention of western lands also reflected broader 19th-century policies regarding territorial development, resource management, and the challenges of governing sparsely populated regions. But the pattern in Utah is hard to ignore: delayed statehood, strategic military positioning, and extensive land retention all worked to limit Mormon autonomy.

So, more than a century on, when Senator Mike Lee proposed selling off land, the controversy tapped into more than partisan land policy. Behind the politics is a deeper, older story about the unrealized legacy of Deseret.

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic, this coming winter). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.