Beyond the 40 Questions, Part 1

3 Things That Changed How I Think About Joseph Smith

With 40 Questions About Mormonism releasing in a matter of days, I wanted to take some time to reflect on how I’ve grown through the process. Writing is more learning than information sharing, and that was certainly the case with this project.

Over the next three weeks, I’ll be sharing some of those reflections.

Up first…

Three Things That Changed How I Think About Joseph Smith

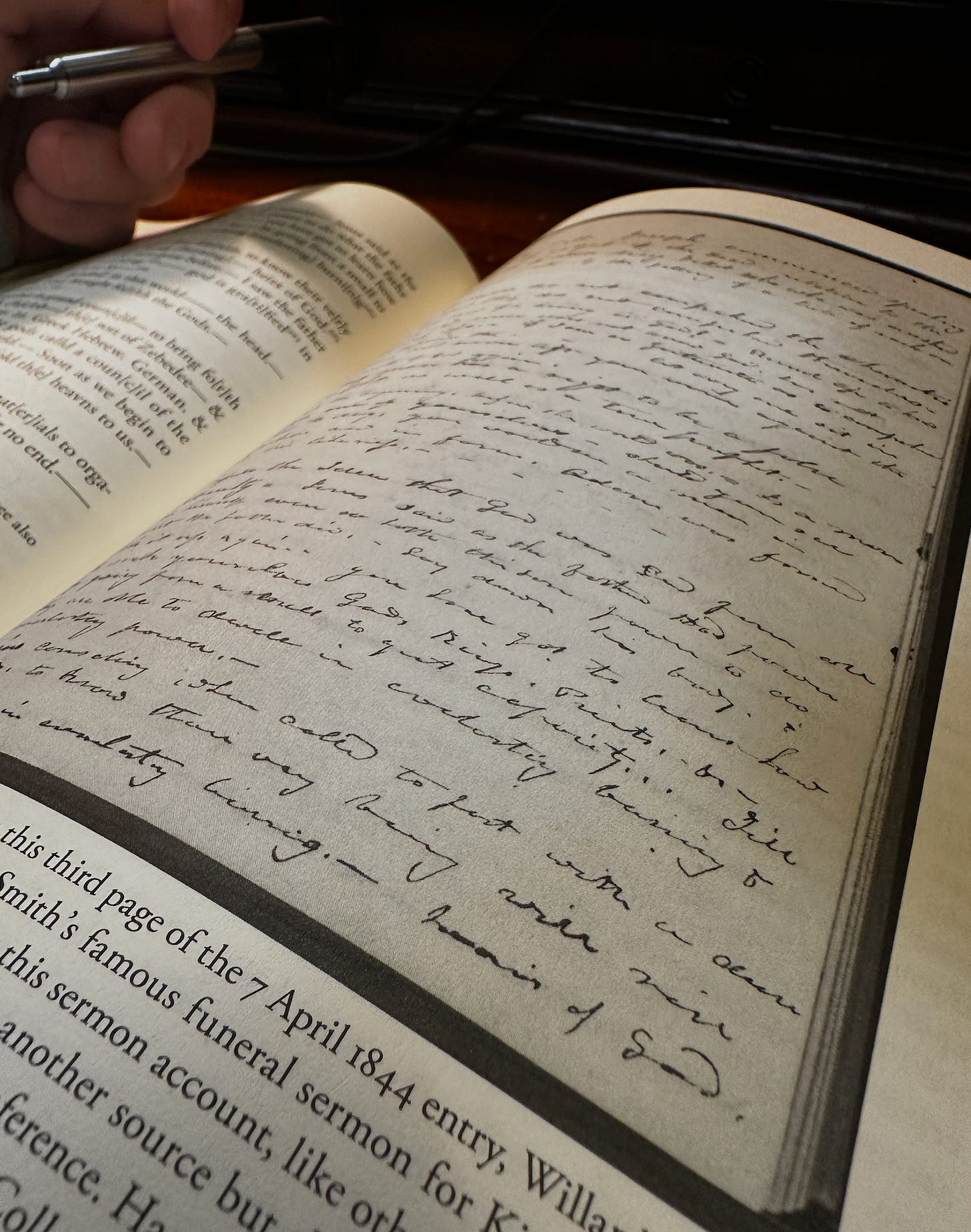

I spent the better part of a year reading many of his journals and personal correspondence. (Special thanks to the Joseph Smith Papers team for making that possible.)

When I did, I was intentional about not reading the revelations he produced or his doctrinal constructions. I read those, of course, but part of me wanted to see the mundane, day-to-day Joseph Smith. To just see him visit with friends, preside over weddings and funerals, pray over sick children, reflect on community tensions, etc.

Honestly, I was expecting to see a man with an abundance of ambition, maybe getting a sneak-peak into the inner-workings of a charismatic religious entrepreneur building an empire. But what I found instead surprised me. Not a prophet, but not a con man either.

Something altogether different.

Joseph Smith Sincerely Desired to Heal Sectarianism

The first thing that changed is this: I believe Joseph Smith was genuinely concerned about his own soul and the fractured state of Christianity on the American frontier of his day. That’s not a statement about whether he was right—I don’t think he was—but about whether he was sincere.

Skeptics of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I’ve found, often assume that Joseph Smith was insane or a charlatan, or a little bit of both. The conman angle is especially popular because it’s cleaner and easier to dismiss.

But, boy, that framing makes it really hard to square away with all the historical details.

Joseph’s early history reveals a young man formed in the Burned-Over District of upstate New York, a cauldron of spiritual ferment where revival fires blazed constantly and competing denominations promised conflicting paths to salvation. His mother, Lucy Mack Smith, remembered him as someone who “always seemed to reflect more deeply than common persons his age upon everything of a religious nature.”

(I don’t know why’d you lie about something like that.)

Joseph’s grandfather, Solomon Mack, underwent a dramatic conversion after years of resisting the gospel, finding rest in Christ after nightly visions and profound conviction of sin. Joseph Jr. found himself in remarkably similar spiritual territory. “I felt to mourn for my own sins and for the sins of the world,” he wrote in his earliest autobiographical account.

And that was compounded by a lack of trust and an abundance of spiritual confusion. He didn’t know which (if any) pastors or ministers or elders he could trust, since they all seemed to contradict one another—e.g., debates over baptism, Calvinism versus Arminianism, the proper mode of worship, the nature of conversion itself.

*Cue Ecclesiastes 1:9

The cacophony of competing voices is a feature of every age.

Most of us—to channel C.S. Lewis here—pick a room (denomination) in the “great hall” of Christianity, and settle in. We find a tradition, make peace with its ambiguities, and stay. But Joseph didn’t; he couldn’t. Rather than settling into one of the available rooms, he began to sense what his contemporaries—the budding Restorationists—called a universal apostasy “from the true and living faith,” evidenced by the “contentions and divisions” among those claiming Christ’s name.

That may sound abrasive, but, again, a lot of his contemporaries thought something similar. Alexander Campbell, for example, surveying the same fractured Protestant landscape, drew his own sharp conclusions about creedal Christianity and the church’s drift from its apostolic roots. “No creed but Christ” became that anti-creedal non-denominational denomination’s creed.

Granted, Joseph went considerably farther than Campbell—I discuss that in the book—but their sentiment, at least, rhymed. Both men looked at the same religious chaos and concluded that something had gone deeply, structurally wrong.

Joseph sincerely want to heal the sectarian nature of the Christianity in which he was raised.

It’s not hagiographic to admit that. Acknowledging his sincerity doesn’t validate his prophetic claims; it’s simply doing justice to the historical record. A man can be sincerely wrong—and I think he was because, ironically, he fractured Christianity even further—but recognizing his sincerity matters for how we understand what actually happened in the past and how we engage contemporary Latter-day Saints who respect and admire him.

The 100% “con man” narrative keeps us from grappling with the serious questions Joseph raised, and the genuine spiritual hunger he both experienced and exploited. If we want to understand why Mormonism succeeded and continues to thrive, we need to reckon with a Joseph Smith who actually believed what he was doing mattered for eternity.

Joseph Smith Was Not a “False Prophet” (With a Major Caveat)

The second thing that changed is how I think about the question itself. I no longer find it particularly helpful to ask whether Joseph Smith was a “true” or “false” prophet.

Hear me out.

When the Bible speaks of true prophets and false prophets, it’s addressing those who claim to speak God’s word to God’s covenant people within the framework of established revelation in the Old Covenant. True prophets like, Isaiah and Jeremiah, called Israel back to Torah faithfulness. False prophets like, Hananiah, prophesied falsely in God’s name. Both operated within the same covenant framework, and both addressed the same people with competing claims about the same God’s intentions. True prophets heralded—whether explicitly or implicitly—the coming of the messiah; false ones, what not to look out for.

But I don’t think that’s what Joseph was doing because he clearly envisioned himself as something more comprehensive.

Joseph claimed to be a latter-day prophet-apostle, modeling his office after Moses and the Twelve. The revelations he produced often emulated OT prophecy with their “hearken” and “behold” formulas, while his letters to scattered saints drew heavily on NT apostolic language and allusions. He described receiving divine words “even as Moses” and being appointed “to preside over the whole church and to be like unto Moses,” if Moses were also Peter. It’s as if Joseph claimed authority above the rank-and-file prophets of the OT.

And there is such an office, a Prophet of Prophets, so to speak. I don’t think Joseph was wrong to recognize that that kind of authority exists; rather, he was simply wrong to claim it.

You see, here’s the critical distinction: from a traditional Christian perspective, the office Joseph claimed is already occupied.

God “has spoken to us by his Son” in these last days (Heb 1:2). Christ is the Word of God incarnate (see John 1:1, 14). He has fulfilled all divine purposes and plans for redemption. The prophetic office, in its ultimate sense, belongs to Christ alone. Just as there is no High Priest on earth, nor King of the Kingdom of God on earth—because both are occupied by Christ—there is no Prophet on earth.

So, it’s not that Joseph Smith was a “false” prophet; he wasn’t a prophet to begin with.

Now, I know how that sounds to a Latter-day Saint—dismissive, a bit arrogant, as though I’m defining Joseph out of contention rather than engaging him seriously. That’s not my intention, and you won’t find that in the book. But consider what I’m actually saying: this is the most basic, most central reason most people aren’t Latter-day Saints. You either believe Joseph’s claims or you don’t.

And someone might object here by appealing to Jesus’s words: “You will recognize them [false prophets] by their fruits” (Matt. 7:16). Jesus seems to indicate that prophets exist, and we are to judge them by their fruit—some “true” prophets, some “false” prophets. So, shouldn’t we examine Joseph’s life to see the kind of fruit he produced, whether good or bad?

Ironically, I think this is like comparing apples to oranges.

In context, Jesus isn’t addressing whether someone legitimately occupies the office of Prophet; rather, he’s giving his disciples a practical test for discerning prophetic speech, or what the NT later identifies as the gift of prophecy, the Spirit-prompted utterance that edifies, exhorts, and comforts the church (see 1 Cor. 14:3). That’s a different thing than whether someone legitimately holds the office of Prophet that the Lord Jesus filled and fulfilled. His warning about fruits is diagnostic for words, not a credentialing mechanism for offices.

Imagine someone besides Donald Trump claiming to be the President of the United States. We wouldn’t call that person a “false president,” as though they were competing for a legitimately open position. We’d recognize they fundamentally misunderstand how the office works. It’s occupied, and their claim doesn’t engage with that reality.

Similarly, Joseph wasn’t competing to be a better or truer prophet within the biblical framework. He was claiming an authority that, from a traditional Christian view, is presently and finally filled in the Lord Jesus.

Just as there is no other High Priest besides Christ, nor King of Kings besides the Lord, there is no Prophet aside from Jesus.

Anyway, this is the position I have come to adopt.

Joseph Smith Was Very Pastoral

The third thing that changed is my appreciation for Joseph’s genuine care for his people. This is perhaps the most surprising shift because it requires saying something positive about a man whose theological legacy I find to be an incredible departure from historical Christian orthodoxy.

But I can’t deny what I read in his private journals and correspondence. In aggregate, they reveal dimensions of Joseph’s character that don’t fit neatly into the villain narrative many people prefer, myself included earlier in life.

He celebrated with newlyweds at weddings, attended the sick at risk to his own health, wept with mourners at funerals. He advocated for victims of domestic abuse, prayed over a crisis pregnancy, consoled a woman whose baby died on Christmas Eve, and, I’m assuming, later presided over the child’s funeral. If you’ve never done that, I can tell you, as a minster, it’s among the most emotionally painful experiences to endure. I’ve buried many faces I can’t remember, but I’ve never forgotten a single child’s face.

And Joseph’s hospitality was legendary—he received so many visitors that he sometimes complained of being “hindered by a multitude,” and yet still prayed, “May God grant to continue his mercies unto my house.”

Joseph Smith was a more hospitable man than I presently am, and that’s a convicting thought.

Moreover, Joseph cultivated sympathy for the afflicted, acted as advocate for the accused during church trials, and genuinely desired to alleviate poverty among his followers. “I feel myself bound to be a friend to all the sons of Adam,” he wrote, “whether they are just or unjust, they have a degree of my compassion and sympathy.”

I think Joseph wanted more than power and prestige. I think he wanted to be a sort of spiritual father figure to a people of his own, a leader who would care for them spiritually and temporally.

This pastoral dimension doesn’t erase his failures. He was, by his own admission, “but a man” who should not be expected to be perfect. But recognizing his pastoral instincts helps explain the fierce loyalty he inspired and the genuine love many followers felt for him even amid his failures.

More importantly for the LDS-evangelical dialogue, it helps us see that people weren’t drawn to Mormonism solely by novel doctrine or charismatic claims, as it sometimes the case in our framing. People were drawn to a community led by someone who—however much I disagree with his theology—demonstrated genuine care for their wellbeing.

I can’t unsee that in the record.

So What?

Ok, these three shifts—recognizing Joseph’s sincerity, moving beyond the true-or-false-prophet framework, and acknowledging his caring side—are big moves for me, personally, and I hope they are a more historically responsible and theologically precise engagement with Mormon origins.

None of this changes my conviction that Joseph Smith was wrong in his central claims. I still believe, for example, that the Book of Mormon is not ancient scripture. But it does change how I approach those convictions and how I invite others into the conversation. And it requires me to remember that real people—my LDS neighbors and friends—revere Joseph as a prophet of God.

Alright, friends, 40 Questions About Mormonism releases next Tuesday (!!!) and is available for pre-order now at Amazon.

In next week’s essay, I’ll explore three things that changed how I think about the Book of Mormon, including why I now believe there were, indeed, physical plates, and an interesting (I think at least) exegesis of the promise in Moroni 10.

The following week, I’ll turn to Mormon theology itself, and what Latter-day Saints might teach evangelicals about Gethsemane.

📘 Coming February 2026: 40 Questions About Mormonism

If you’ve appreciated this essay, you’ll love my forthcoming book, 40 Questions About Mormonism (Kregel Academic). It’s written for traditional Christians who want clear, charitable, and biblically faithful answers to the most common questions about the Latter-day Saint faith and tradition.

PRE-ORDER TODAY and download three free chapters while you wait.

I'm glad to see you dig deeper and consider broader elements. Over the years I've come to the conclusion that many evangelicals are only concerned about an inch-deep understanding of and engagement with Latter-day Saints, focusing on our concern for orthodox doctrine from our historic perspective of Christendom rather than LDS perspectives. If we are really serious about our concerns and our LDS neighbors we should dig more deeply. You have participated in this project via looking historically at Joseph Smith to understand the man behind the LDS Church and the ensuing "cult wars," but we can go even deeper. My hope is that evangelicals might also consider that the LDS really aren't doctrinally oriented, and for them there is greater concern for ritual, ethics, narrative, and the arts. Years ago I had a conversation with my LDS colleague at the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy where we discussed our traditions, and we came away with an understanding that Protestants tend to approach their tradition like philosophers, whereas LDS are generally more like artists (e.g., pageants in the past). We need to learn how to try to understand others as they understand themselves rather than as heretical mirrors of our concerns.